Giuseppe Verdi - Ernani

Teatro Regio di Parma, 2005

Antonello Allemandi, Pier' Alli, Marco Berti, Carlo Guelfi, Giacomo Prestia, Susan Neves, Nicoletta Zanini, Samuele Simoncini, Alessandro Svab

C-Major

George Bernard Shaw may or may not have had Ernani in mind when he came up with the generic definition of an opera plot as being about a tenor and a soprano who want to make love but are prevented from doing so by a baritone, but Verdi's opera matches this description remarkably closely. Based on Victor Hugo's historical drama, 'Hernani', Verdi's Ernani is very much a product of its time, seeped in arch-romantic sentiments of honour, nobility, love, duty, betrayal and revenge, and Verdi's musical treatment of the subject can be seen as somewhat academic, adhering closely to the Italian operatic tradition of the time, writing for particular voices in certain roles. It's how the voices are used in this work however that makes all the difference.

What distinguishes Ernani from other historical romantic dramas of this type, and provides a degree of variation from the GB Shaw template, is that there is not just a tenor and a baritone competing for the hand of the soprano in question, but Verdi also makes use of a bass as an extra cog to his musical wheel. What makes Verdi's handling of the subject interesting in this early work of the composer however is not so much the apportioning of those characters to the conventional singing roles, but in how Verdi develops the musical expression of those types in a way that would determine and set archetypes that he would often come back to over the years, particularly in how he manages to brings them together into a single musical and dramatic unit.

Essentially then, for all the romantic exoticism of the Spanish setting, with Don Juan of Aragon forced into hiding and taking the disguise of the bandit Ernani, his romance with Elvira under threat not just from her impending marriage to Don Ruy Comez de Silva, but from a rivalry with king in waiting Don Carlo, Ernani fits very much into the mold of the by-the-numbers romantic melodrama. It would be certainly lacking in any kind of dramatic credibility that would engage a modern-day audience where it not for Verdi's skillful writing for the voices. Working for the first time with the poet Francesco Maria Piave, Verdi taking the upper hand with a clear idea of how he wanted to express the drama, Ernani is consequently wonderfully structured and skillfully arranged, the scenes played out with musical consistency and fluidity that doesn't call for the action to be halted in order for the singers to step forward and do their singing pieces.

Or at least, ideally, that's how Ernani ought to be played. With the right kind of singers and direction, it shouldn't be as dramatically rigid as it is presented in this 2005 production for the Teatro Regio di Parma, but unfortunately, neither the singers nor the direction are fully up to the task. Directed by Pier' Alli, the set and costume designs are old-fashioned and period - which is fine and suits this particular work - but there's no reason why it should also be presented in the old-fashioned 'park and bark' style, the singers all standing, looking out, gesturing and delivering the lines as if there were asides to the audience rather than directed towards the other characters in the drama. In some cases the drama can indeed to be rather expositional and declamatory, but through duets, trios and choral arrangements, and in the very tone and blending of the voices, Verdi strives to make it much more interpersonal - but in order to achieve that, you don't just need stronger direction and some dramatic input from the cast, you also need good singers.

It's for this reason that I used the term 'park and bark' above rather than 'stand and deliver' to describe the performances, because, unfortunately, there's more barking than nuanced or even accurate delivery of Verdi's vocal writing, and the weakest elements are actually the roles where it really needs to be tighter and more expressive - Elvira and Ernani. Marco Berti and Susan Neves both have their

moments - Neves notably in the highly-charged third scene where she

holds steady alongside the imposing Carlo of Carlo Guelfi and the grave

intonations of Giacomo Prestia's Silva, but elsewhere they are

terribly uneven. Guelfi is undoubtedly the best there is here,

bringing a real sense of the power, danger, nobility and clemency that

his character proves to be capable of, but alone and under this stage

direction, it's never enough to convey the true worth of the

arrangements.

The singing and the staging leave something to be desired, and unfortunately the musical presentation under Antonello Allemandi is similarly uneven. This is certainly disappointing and surprising, as the Allemandi and Alli team work much better together in the Teatro Regio di Parma recording of Oberto that is also available on Blu-ray as part of this collection. This isn't entirely a bad performance of Ernani, just a rather uneven one that at its best never really rises above merely average. Ernani however, for all its flaws as one of Verdi's earliest works, surely deserves more than that.

This recording of Ernani (previously released on DVD by Dynamic) is released here upgraded to HD in a Blu-ray release as part of the 'Tutto Verdi' series from C-Major, a collection that is made up of performances of all Verdi's opera work recorded at the Teatro Regio di Parma. Some trailers for other works in the collection are included on the disc, as well as a visual introduction/synopsis for Ernani. The quality of the HD image is generally very good, although one or two scenes lack the same kind of detail that can be seen elsewhere and some of the camerawork is a little bit rough in places. There are no problems with the audio tracks, both the PCM Stereo and DTS HD-Master Audio 5.1 sound clear and strong. There are however one or two curiosities in the English subtitles, but nothing significant. The Blu-ray is all-region, with subtitles in Italian, English, German, French, Spanish, Chinese, Korean and Japanese.

Giovanni Battista Pergolesi - Il Flaminio

Teatro Valeria Moricone, Jesi, 2010

Ottavio Dantone, Accademia Bizantina, Michal Znaniecki, Juan Francisco Gatell, Laura Polverelli, Marina De Liso, Sonia Yoncheva, Serena Malfi, Laura Cherici, Vito Priante

Arthaus

So far we've had two excellent productions from the Fondazione Pergolesi Spontini at Jesi that have extended appreciation of Pergolesi's opera seria work - Adriano in Siria and Il Prigionier Superbo - and in the process shed a little light upon the practices of 18th century Neapolitan opera with their Intermezzo comedies. For anyone who has enjoyed the lighter side of Pergolesi's work seen in these shorter pieces, Il Flaminio is a real treat. A full length 3-act commedia per musica, first performed in 1735, it's every bit as delightful as the great Intermezzos seen so far - Livietta e Tracollo and La Serva Padrona - and, in its own way, quite sophisticated and just as revelatory as the composer's more serious works.

There is, it has to be said, nothing that appears to be exceptional about the plotting of Il Flaminio. The widow Giustina has been set on an engagement to the noble but rather frivolously-minded Polidoro, but has fallen instead for his friend Giulio, who she recognises as Flaminio, a Roman gentleman she once knew before she met her husband. Back then however, she despised Flaminio, which may account for why "Giulio" is reluctant to accept that her feelings might have changed in any way. To complicate matters - always essential in such a situation - Polidoro's sister Agata is in love with Giulio and cruelly rejects her intended Ferdinando, but her feelings are not reciprocated by Giulio. On the sidelines, watching and intervening in the situation - not disinterestedly, since the possibility of their union depends to some extent on a resolution of these issues - are Checca and Vastiano, the maidservant of Gustino and the manservant of Polidoro.

Il Flaminio therefore still adheres very much to the Metastasian baroque opera seria situation - one not dissimilar to the one played out in Pergolesi's Adriano in Siria - where various incompatible couples have to find their right arrangement over the course of the opera, usually on a wise ruler coming to his senses (it's a nobleman Polidoro here), but only after a great deal of emotional soul-searching and pouring one's heart out through anguished, repetitive arias. The difference here in Il Flaminio is that this time the situation is explored for its comic potential, playing the situation for laughs certainly and with a lightness of touch, but not to the exclusion of the finer sentiments that lie within it either. That in itself is a significant development and influential in terms of the impact the Neapolitan style would have on opera buffa, but in Pergolesi's hands, one can also see a significant development of the writing and the scoring that goes way beyond the Baroque conventions.

The comic elements may be partly based around class issues, but the comedy in Il Flaminio proves to be rather more sophisticated than La Serva Padrona (as important to the history of opera as that work remains). Much of the humour is tied to the use of Neapolitan dialect and customs on the part of the lower classes, with obscure satirical references and musical allusions to popular songs of the time, to puppet shows and commedia dell' arte traditions that are impossible to translate or even fully appreciate. One can at least - having been in a position to see similar situations played out in the Baroque works of Handel and Vivaldi - appreciate how the complex relationship drama is satirised by the comedy. "I forsee suffering and misery for me", Guistina observes at the start of Act I - "Why worry?" responds her maidservant Checca, "Everything will turn out fine in the end".

There's only so much humour to be derived from this really though, particularly over a three-hour opera. To be honest, I lost interest in following the plot by the middle of the second act, but thankfully there's more to Il Flaminio than mild comedy and satire, and Pergolesi's beautiful music makes such light work of the situations and is filled with such playful invention and sophistication that there is never a dull moment. It's way ahead of its time, Pergolesi's handling of material we are familiar with from Handel and Vivaldi only highlighting just how much more musically advanced and innovative the composer really is above his contemporaries. It's not just the stormy accompaniment to Giulio's vigorous Act I aria 'Scuote e fa guerra' ("May shake and make war the ruthless wind"), or even that Pergolesi imitates the mewling of a cat in Bastiano's Act II aria - delightful though those kinds of little touches are - but there's such a lightness and brilliance of sophistication throughout Il Flaminio that it could easily pass for a Haydn or an early Mozart opera. It really is extraordinary.

It's even more delightful then that we have Ottavio Dantone and the Accademia Bizantina to bring out the sparkling brilliance and delicate beauty of music that is so full of life, vigour, wit and sensitivity. The wonderful set design moreover places the orchestra behind the performers on the stage in a venue that has been reconfigured with extensions that take balcony scenes down the sides of the hall to make it even more intimate and involving. It looks great and it evidently works marvellously since the singing and acting performances are also highly engaging and entertaining. Although there are pieces written to give each of the singers the opportunity to shine, Il Flaminio is very much an ensemble piece that gives equal value to almost all the roles and - as with each of the Jesi Pergolesi releases so far - the casting and singing is perfect. Recognising that the strength of the opera is in its ensemble arrangement, the production also attempts to keep all the main figures around on the stage - along with the orchestra - even when they are not called upon to sing.

As with the previous Pergolesi releases - from both Opus Arte and Arthaus - the recording quality is superb, with a beautiful High Definition image and remarkably good sound quality. Really, it's hard to imagine how you could improve on the performance or presentation of this rare work, a work that fully merits such a wonderful interpretation. There are no extra features on this release however, which is a little disappointing, but there is some useful background information on the work in the booklet that comes with the release. The Blu-ray is all region compatible with subtitles in English, German, French, Italian, Spanish and Korean.

Gioachino Rossini - Zelmira

Rossini Opera Festival, Pesaro, 2009

Roberto Abbado, Giorgio Barberio Corsetti, Alex Esposito, Kate Aldrich, Juan Diego Flórez, Gregory Kunde, Marianna Pizzolato, Mirco Palazzi, Francisco Brito, Sávio Sperandio

Decca

Rossini's final opera written for Naples, Zelmira, is rather less well-known now than the greater works written for Paris that immediately follow it - Moïse et Pharaon, Le Comte Ory, Guillaume Tell. It's an opera that places exceptional demands on the singers, but perhaps no more so than those later works, so that only accounts for part of the reason why it so rarely performed. Produced for the Rossini Opera Festival in 2009, the problems with staging Zelmira would seem to derive from the nature of the work itself as an opera seria. It's a long work that follows the format of set scenes and emotions that presents challenges that even the musical invention of Rossini or strong singing performances alone can't overcome. It needs to work dramatically, and unfortunately, Giorgio Barberio Corsetti's messy and confused production for Pesaro doesn't do much to help it.

Although there are claims by Roberto Abbado and the Pesaro Festival organisers that Rossini's music here extends the constraints of opera seria, the structure remains largely intact, and Rossini in reality does little more than play around to bring the form of the da capo aria into what we associate today with bel canto ornamentation. There are some terrific arias and arrangements here in Zelmira, but there is nothing that Rossini hasn't already taken much further and with better dramatic integrity in earlier work for Naples like La Donna del Lago. The music for Zelmira for the most part - in between the showpiece arias - remains fairly rigid and lacking in variation, building from a canter to a gallop in that famous Rossinian style to create a rising emotional intensity, but its peaks are ill-served and ill-matched to an unexciting plot.

The main problem lies with the fact that the overall structure of the piece is weighed down by the unwieldy conventions of the opera seria form. The plot of Zelmira is mechanical and improbable, relying on standard situations, coincidences and actions that arise from rather one-dimensional character development. In the tradition of Baroque opera, the main dramatic drivers of the action have already taken place even before the opera even starts. Set on the isle of Lesbos, a struggle for power has erupted while Ilo, the husband of Zelmira, has gone to defend the homeland. Azor, the Lord of Mytilene, has launched an attack, burning down the temple of Ceres, where Azor has been led to believe - on the word of Zelmira - that her father, King Polidoro is hiding. Zelmira however has secured her father secretly in the royal mausoleum. Antenore takes advantage of the situation, killing Azor, laying claim to the throne himself and he accuses Zelmira of being complicit in the death of Azor and her father, the king, as well.

Now there are plenty of opportunities for Zelmira to prove her innocence during Act 1 of the actual opera, but Rossini forgoes any realistic dramatic progression to the conventions of opera seria where everyone laments the current state of affairs in arias adorned with repetition and ornamentation. The troops lament the death of Azor, Polidoro is distraught and broken alone in his hiding place, while Zelmira's protests of innocence fall on deaf ears. Amazingly, there seem to be no witnesses among the public or the troops to back up her claims, and even faced with imprisonment, Zelmira doesn't seem to be in any hurry to reveal that the king is not actually dead. She is at least able to eventually convince her confidante Emma to take her young son into hiding.

Even when her husband Ilo returns to his homeland (delivering one of Rossini's great arias - 'Terra Amica'), Zelmira's actions only seem to dig her in deeper and it's Antenore and his lieutenant Leucippo's account that Ilo is told. In one of those improbable situations that only occur in opera then, Zelmira - attempting to rescue Ilo from assassination by Leucippo, ends up with the dagger in her own hand and has another crime to answer for. Inevitably, it's going to take a few more rounds of arias to assimilate the enormity of this new heinous act and the kind of conflicted emotions it engenders in each of characters, before Zelmira eventually produces Polidoro and her son, and the villains are found out.

Ostensibly then Zelmira is very much in the tradition of the opera seria, dealing with rulers, power, corruption and lies, but in reality, as the title of the opera derived from the name of the heroine suggests, it's more about the heroine, Zelmira. Faced with injustice, false accusations, her innocence and integrity called unjustly into question, Zelmira is very much the early prototype for the bel canto heroines of Donizetti and Bellini. As such, and particularly in how it holds closely to the opera seria style and stretching as it does to three and a quarter hours in length, Zelmira can be a bit of a stretch for anyone interested in strong character development and dramatic credibility, but it does have other compensating factors in the inventiveness of Rossini's arrangements, the musical colours that he brings to the genre and the opportunities that this provides for the singers to imprint personality and character onto the work through their singing delivery.

If Kate Aldrich isn't quite able to make her Zelmira work, it's through no fault of her singing which has real power and expressiveness, but rather more of a question of this being a role that requires a singer of greater stature and personality to bring it to life and make her predicament credible and sympathetic. The same challenge faces all the singers here, but in their case, they really need better stage direction and a better production design than the one provided here. Juan Diego Flórez has plenty of personality and the range to meet the demands of this kind of Rossinian role - strong, resonant, wonderfully musical and expressive, but his high timbre is never the most pleasant and it's not helped by the acoustics of the stage (set up in Pesaro's Adriatic basketball arena) and sounds quite squeally at the high notes in a way that is hard on the ears. The sound suits the bass and bass-baritone voices much better, giving a lovely resonance to Alex Esposito's grave Polidoro and Mirco Palazzi's Leucippo, whose recitative even sounds beautifully rounded and musical. Gregory Kunde however also comes across well as Antenore, and Marianna Pizzolato almost steals the show with her luxurious mezzo-soprano in the contralto role of Emma.

With a cast this good, a stronger production might have made all the difference, but Giorgio Barberio Corsetti's concept doesn't seem to suit the character of the work. Instead of Zelmira's predicament, the focus is very much upon the nature of war and power, the director setting the production in near darkness, using overhead mirrors to reflect the darker and hidden side of all these power struggles and lies that we don't normally see, reflecting wounded, tortured and dead troops placed beneath the grilled stage. Apart from not really helping the opera where it needs the support, it actually works against it, making it seem very messy, unfocussed and often downright ugly.

It may have looked better in the theatre, but the darkness of the stage, the figures highlighted in pale yellow light, with confusing reflections in the background mirrors, doesn't come across well on the screen, even in High Definition. There appears to be some post-production adjustments to balance the contrasts, and even shadowing applied to block out the frequently visible conductor Roberto Abbado at the front of the stage, but this only proves to be even more distracting and messy. The PCM Stereo and DTS HD-Master Audio 5.1 tracks on the Blu-ray disc however are mostly fine, even if there is some harshness in the reverb of the acoustics. The Decca BD also includes a 25-minute Making Of, which contains interesting thoughts and information on the work itself and the production from the cast and the production team.

Giuseppe Verdi - Un Ballo in Maschera

The Metropolitan Opera, New York, 2012

Fabio Luisi, David Alden, Sondra Radvanovsky, Kathleen Kim, Stephanie Blythe, Marcelo Alvarez, Dmitri Hvorostovsky, Keith Miller, David Crawford

The Met Live in HD, 8th December 2012

Verdi's Un Ballo in Maschera (A Masked Ball) is an opera of wild dynamism, marrying together scenes of jarring contrasts in a way that makes it difficult opera to stage dramatically and musically in any coherent or consistent way. It certainly not an opera I've seen handled convincingly on the stage, but David Alden's production for the Metropolitan Opera, if it doesn't quite bring it all together, at least points towards a way that might work. Not playing it entirely straight, not playing it up for laughs either, but playing it scene by scene the way Verdi wrote it.

Quite what Verdi's true intentions for the work were is of course open to speculation. The work, originally entitled Gustavo III, based on the real-life historical assassination of King Gustav III at a Masked Ball in Sweden in 1792, was notoriously banned by the strict censorship laws of the period in revolutionary Risorgimento Italy, who were unhappy about the depiction of an assassination of a monarch, forcing Verdi to rewrite and rename the characters involved. Even then, the changes applied to the new version, called Una Vendetta in Dominò, weren't enough to appease the censors in Naples, so a furious Verdi took the work to Rome where it was first performed with the setting changed to Boston in North America as Un Ballo in Maschera in 1859. The work is now performed, as it is here at the Met, in its original Swedish setting, but clearly Verdi was forced or felt the need to make compromises to the work in order to avoid censorship even in Rome.

None of this however is likely to have had much of an impact on Verdi's choices for the musical scoring of the piece and, seeking to show off his range and work with musical arrangements and arias more along the lines of La Traviata than the more through compositional style that he was gradually moving towards, Un Ballo in Maschera consequently has some of the composer's most beautiful melodies, striking arrangements and dramatic situations. Every dramatic situation is pushed to its emotional limits - whether it's the love of Gustavo for Amelia, the wife of his secretary, the friendship of Gustavo and Renato which is to fall apart on the discovery of the affair, or the hatred felt by the king's adversaries - all of it is characterised by Verdi with an extravagance of passion.

An extravagance of melody too which, accompanying the melodramatic developments of the plot's regal and historical intrigue, to say nothing of incidents involving gypsy fortune tellers, can lead the work to switch dramatically at a moment's notice between the most romantic of encounters to the deepest gloom, from declarations of love to dire threats of vengeance. The key to presenting the work coherently - if it's at all possible - is to try to ensure that these moments don't jar, and with Fabio Luisi conducting the orchestra of the Metropolitan Opera here, musically this was a much more fluent and consistent piece than it might otherwise have been, without there being any alteration or variation to the essential tone of the work.

Inevitably, any director is going to look for a consistency of style in the approach to the stage direction, but that's probably a mistake with this work. It's not a mistake that David Alden makes. I must admit, having seen Alden's fondly humorous day-glo productions of Monteverdi's L'Incoronazione di Poppea and Handel's Deidamia, I had a suspicion that Alden might settle for playing up the camp comic side of Un Ballo in Maschera - which is certainly there and probably a more convincing way of playing the work than attempting to do it completely straight if the Madrid Teatro Real production is anything to go by - but I was wrong. Alden plays every single scene in accordance with the tone established by Verdi, light in some places, thunderingly dramatic and brooding in others, but always operating hand in hand with Fabio Luisi to ensure that this can be made to work musically and dramatically.

Where the staging has consistency of theme and a consideration for a meaningful context for the work however, was in Alden's typically stylish and stylised production designs, created here by set designer Paul Steinberg and costume designer Brigitte Reiffenstuel. Evoking a turn of the twentieth century setting that takes the work entirely out of its historical context (notwithstanding the personages reverting to their original Swedish names), the production had the appearance of a Hollywood Musical melodrama, as lavishly stylised as a Bette Davis melodrama, but consistent within its own worldview, and it worked splendidly on this level. The set was a little overworked in places, with dramatic boxed-in angles and heavy Icarus symbolism in a prominent painting, but it clearly responded to the nature of the work, playing more to the sophistication that's there in the music than the often ludicrous libretto. Alden however even found a way to incorporate this into the production with little eccentric touches - such as the eye-rolling madness of Count Horn, which is not a bad idea.

Similar consideration was given towards the singing and the dramatic performances of the cast assembled here, which was - as it needs to be - forceful and committed. The combination of voices was also well judged, the Met bringing together a few Verdi specialists well-attuned to the Verdi line - Marcelo Álvarez (who I've seen singing the role of Gustavo/Riccardo before), Sondra Radvanovsky and lately, Dmitri Hvorostovsky - all of them strong singers in their own right, but clearly on the same page as far as the production was concerned. A few regular Met all-rounders like Stephanie Blythe and Kathleen Kim also delivered strong performances in the lesser roles of Madame Arvidsson and Oscar that really contributed significantly to the overall dynamic. This was strong casting that brought that much needed consistency to a delicately balanced work where one weak element could bring the whole thing down.

Alden and Luisi were clearly aware of this and played to the strengths of the charged writing for these characters. Act II's duet between Álvarez and Radvanovsky was excellent, hitting all the right emotional buttons, each of the characters delving deeply to make something more of the characters than is there on the page of the libretto. Hvorostovsky brought a rather more tormented intensity to Renato in his scenes with Radvanovsky's Amelia that seemed a little overwrought, but this paid off in how it made the highly charged final scene work. Un Ballo in Maschera is still a problematic work, but with Luisi and Alden's considered approach and this kind of dramatic involvement from the singers, the qualities of the opera were given the best possible opportunity to shine.

Claude Debussy - Pelléas et Mélisande

Opernhaus Zürich, 2004

Franz Welser-Möst, Sven-Eric Bechtolf, Rodney Gilfry, Isabel Rey, Michael Volle, László Polgár, Cornelia Kallisch, Eva Liebau, Guido Götzen

Arthaus Musik

The 2004 Zurich production of Pelléas et Mélisande is a curious one, but then Debussy's only complete opera is a strange and enigmatic work. It's a work that is founded on ambience and ambiguity, as much in the libretto - Maurice Maeterlinck's symbolist drama brought over almost intact - as in the haunting qualities of Debussy's music, which do not underscore or emphasise specific emotions in the traditional manner as much as suggest otherworldly mood and mystery in the hidden depths that lie within it. The production design consequently also goes for a non-specific, otherworldly location within a snow-bound world that seems to work well with Debussy's floating lines, the coldness and detachment of the expressions, as well as the enclosed intimacy and oppressiveness of the subconscious passions that underlie them.

By far the strangest element of Sven-Eric Bechtolf's production however is the use of life-size dummies, looking uncannily like the characters themselves, which are carried around by them or maintain a presence throughout the performance. Not only are these dummies carried around, sometimes propelled around the stage in wheelchairs, but the characters interact more with the dummies than the actual people they represent. The key to this, of course, is that they are indeed representational and symbolic - the word symbolism deriving from a separation into halves between the real and the representational - and this feels entirely appropriate within an opera that, derived from a symbolist drama, is about much more than the surface interaction between the characters. The idea emphasises not only a failure to connect meaningfully with the other characters, but that they even suffer from a sense of detachment from their own sentiments and feelings.

This is expressed wonderfully within the drama itself in a number of enigmatic scenes that rely on creating resonances and sensations, and Debussy adds to the growing sense of unease through his unsettling scoring and linking musical interludes. Rolf Glittenberg's set designs for the Zurich production, although strange, create an equally unsettling and ambiguous atmosphere that works well with the nature of the work, while even the strange marbled stone suits worn by the inhabitants of the royal castle (but not Mélisande) raise questions or create impressions about their inner nature.

The minimalism, the symbolism and the obsessive repetition, all emphasised in this production through the division between the disembodied figures and their mannequins, seems to reflect a similar haunted quality to the one in Robert Wilson's distinctive production of this opera, where the characters seem to be ghostly figures acting out roles and gestures that have been played out many times before, perhaps at the instigation of Golaud - or even obsessively inside his own head - though his inability to discover, or recognise "the truth". There's a fatalistic quality in the work that bears out this idea, Arkel in particular for example mentioning, at the news of Golaud's marriage to Mélisande - the woman with no past - that "we only ever see the reverse side of destiny, the reverse even of our own", that Golaud "knows his future better than I", and that "perhaps nothing that happens is meaningless". These figures all seem to be searching for meaning and significance in objects, in rings, in towers (a Citroen car here), in a golden ball, and even in the indecipherable blank expressions of dummies. By the end they seem to be no nearer to an answer and the eternal mystery of Pelléas et Mélisande persists.

The production design won't be to everyone's taste, but this is a good all-round performance of the opera. Franz Welser-Möst conducts the Zurich orchestra marvellously through the beautiful floating score with a mood and tempo that matches the ambience of the snow-smothered production and the fluid revolutions of the set. The singing and the performances are excellent, particularly Rodney Gilfry, who seems to delve deeply into the character as Pelléas, but Isabel Rey is also a fine Mélisande, Michael Volle a particularly tormented Golaud, bringing a remarkable intensity and much needed dynamic to the work, and László Polgár brings deep beautiful tones, to a dignified but somewhat opaque Arkel.

The Blu-ray release from Arthaus is a repackage of the previous TDK release, retaining even the label on the disc itself and the original TDK menus. The HD picture quality is very good, the sound well distributed with a cool tone on the PCM Stereo and DTS HD-Master Audio 7.1 mixes. There are no extra features on the disc itself, which is region-free. Subtitles are in English, German, French, Spanish and Italian.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart - The Magic Flute

Scottish Opera, 2012

Ekhart Wycik, Sir Thomas Allen, Nicky Spence, Claire Watkins, Rachel Hynes, Louise Collett, Richard Burkhard, Mari Moriya, Laura Mitchell, Jonathan Best, Peter Van Hulle

Grand Opera House, Belfast - 1 December 2012

If you want to, you can consider The Magic Flute to be a complex work, and with all the qualities that make up the complex personality and musicianship of Mozart placed within it, it most certainly is a work of incredible richness and variety. Written however with Emanuel Schikaneder as a popular Singspiel, what Die Zauberflöte should be above all else however is witty, charming, funny and entertaining. It has a serious side of course, and a meaningful message to put across - and it does get a little bogged down in solemnity on occasion - but it's the means by which those ideas are put across that is essential to the brilliance of the work. Comedy, in The Magic Flute, proves to be a much more effective means of getting that across. And music - but I'll come to that as well.

The light-hearted side of Mozart in Die Zauberflöte can often be undervalued and underrepresented, but the Scottish Opera's production - seen here in Belfast at the end of the tour on 1st December - gets the balance just about right. That's a tricky balance to maintain in this work. How, for example, do you account for all the mysticism, the Masonic initiation rituals and grand solemn ceremonies that undoubtedly underpin most of the enlightened ideals that make up the fabric of The Magic Flute, while at the same time making it accessible and entertaining to a modern audience? How do you reconcile the Tamino and the Papageno? Mozart does the hard bit through his remarkable music, showing love to be the most ennobling and life-affirming act that any human being is capable of, but finding a way to make that work in a setting that accounts for all the trappings of the Masonic rituals is a more difficult prospect for a modern production.

Directing for the Scottish Opera, Sir Thomas Allen's idea isn't a bad one, setting the story up as a kind of fairground show in a Victorian "Steampunk" setting with gentlemen in stovepipe hats, operating pulleys and clockwork mechanical constructions. Visually it's a delight, creating the right kind of 'magical' background that accounts for freaks and animals, smoke and mirrors, but the steam engineering also feels utterly appropriate to the idea of human ingenuity, progress and man's ceaseless endeavours to better himself. It doesn't go all the way to differentiate and clarify the natures of the opposing forces of the Queen of the Night and Sarastro, or establish where dragon slaying fits into the picture, but it's more important to provide a suitably "fun" setting that better engages the audience and allows the story to flow in a relatively consistent manner.

And who better to engage with the audience than Papageno? Well, the Scottish Opera played an interesting trick in making Tamino a regular member of the audience also, picked out sitting in the Circle by a spotlight during the overture and invited to join in the fun on the stage. Tamino can be a little too earnest a figure to entirely identify with, so some pantomime-style banter with the audience on the part of both Tamino and Papageno - and engaging performances from Nicky Spence and Richard Burkhard - helped break down those barriers between the characters and the audience, which is really what The Magic Flute is all about. It's about showing what noble sentiments and actions any man is capable of, whether Prince or fool. Or indeed woman.

Much scorn is poured upon womankind in The Magic Flute, no doubt in line with Masonic tradition - but Mozart's truly enlightened attitude (and I'm sure his love for women) shows that they also have an important part in directing the progress of all mankind on to better things. If there's any doubt about the work's intentions towards women, one need only listen to the remarkable music that Mozart scores for the female figures. The masculine characteristics are straight, direct and measured in both their nobility and, in the case of Papageno, playfulness, but the women bring a wildness, an unpredictability and a sense of abandon - most notably in the case of the Queen of the Night's coloratura and range, but also in the sentiments that plunge Pamina from the heights of love to the depths of despair within the span of minutes, a descent that was handled well in this performance by Laura Mitchell.

All of this is part of what The Magic Flute is about, so in addition to making it look engaging and entertaining, it needs to musically take you on this journey, and on all accounts the Scottish Opera's production was sympathetic to the rhythms and moods of the piece. There were a few curious lapses in tempo that, for example, drained the intensity both from the Queen of the Night's entrance and from Sarastro's grave pronouncements. If they were to give the performer's room to approach the demands of their ranges, it may have been necessary, but Mari Moriya and Jonathan Best didn't seem to have too many problems in these tricky roles. All of the main performers then managed to strike that balance exceptionally well, matching the tone and sentiments of Mozart's writing, and they were well supported by the rest of the cast, with a strong trio in the three Ladies, but also the exceptionally beautiful harmonies produced by the three Boys for this performance.

If there were any minor concerns about the limitations of the fairground setting or in the singers meeting the exceptionally high standards of the work's vocal demands, it's more the spirit and the heart of Mozart's music that is essential to getting the wonder of The Magic Flute across, and the Scottish Opera's heart was in the right place here.

Giuseppe Verdi - Un giorno di regno

Teatro Regio di Parma, 2010

Donato Renzetti, Pier Luigi Pizzi, Guido Loconsolo, Andrea Porta, Anna Caterina Antonacci, Alessandra Maranelli, Ivan Magri, Paolo Bordogna, Ricardo Mirabelli, Seung Hwa Paek

C-Major

Popular wisdom would have it that Verdi was not entirely at home in the genre of comic opera, and history more or less backs this up. You could say that it took him all his life to get to the stage where he was capable of bringing the full wealth of his talent and ability to the genre in his magnificent final work, Falstaff. It's possible also though that it took that length of time for Verdi to get over the abject failure of his first attempt at comic opera writing with his second work, written when he was 26 years old - Un giorno di regno.

A 'melodramma giocoso in due atti' - a comic melodrama in two acts - there are indeed some operatic conventions found in Un giorno di regno that one would not associate with the typical Verdi opera (harpsichord-accompanied recitative!), but unfortunately - in as much as they prove to be inappropriate for comic writing - there are also touches that are very much characteristic of the composer. In Verdi's hands neither prove helpful to the making the opera work, but a strong stage production and good singing at this very rare performance of Un giorno di regno at the Teatro Regio di Parma make this a fascinating experience even if it can't quite go as far as rescuing the reputation of Verdi's early failure.

There's not much one can do however about the fact that the comedy element of Un giorno di regno is really not that funny in the first place. Set in France, around 1733, the Chevalier Belfiore is staying at the Château of Baron Kelbar in the guise of Stanislas, King of Poland, while the real Stanislas secretly leaves the country to return to defend his throne. Belfiore wants to drop the disguise as soon as possible, since the baron is about marry his widowed niece, the Marquise del Poggio, to Count Ivrea. Belfiore is in love with the Marquise, but since he has disappeared to take on the role of Stanislas, she believes that he has abandoned her - although the king looks strangely familiar to her. To add further confusion to the romantic complications, the baron has planned for a double wedding to marry his daughter Giuletta to the Treasurer, La Rocca. Giuletta however is in love not with La Rocca, but with his nephew Edoardo, who loves her in return, but is poor and therefore an unsuitable match.

It's a standard comic set up of the romantic complications that arise from arranged marriage mismatches and secret or hidden identities of characters in disguise. The twist in Un giorno di regno, which could be translated as 'King for a Day', is that Belfiore realises that he can take advantage of the powers that he has been temporarily gifted with on the blessing of Stanislas, and has the ability to make some royal commands and appointments that will sort out the business between Giuletta and Edoardo. As for his own romantic situation, well, he can only hope that his "reign" will end in time for him to reveal his true identity and claim the hand of the Marquise.

It's not a plot that is entirely bereft of comic potential. Rossini had to make much out of thinner material than this, and Verdi seems to have at least learned that much from Rossini, scoring with vigorous arrangements that build in tempo towards explosive ensemble finales. Verdi however lacks Rossini's lightness of touch, and what would be an amiably riotous situation in a Rossini opera, rises into a rousing bombastic declamation in Verdi's hands. While it's fascinating to see just how Verdi develops those situations in his own distinctive way - particularly with a view to what comes later in the composer's career - they prove however to somewhat work against the comic potential. In one scene, for example, where the young love has been frustrated by the plans of others for personal and political gain, you can hear Verdi straining for the melancholy tragedy of Don Carlos or La Traviata, instead of playing up the comic element of the contrast between La Rocca drawing up military plans while the real "enemy", Edoardo, woos his intended Giuletta. The music is gorgeous and cleverly arranged, but it doesn't really establish the right kind of buffo tone that is required by the situation.

Neither really does the stage direction. The best thing you can say about Pier Luigi Pizzi's direction is that it is unobtrusive and doesn't draw attention to itself in any way that detracts from the musical drama. It's generically opera period in design and costumes, with columns, bookcases and tables that reflect the mansion locations and gardens, and it's well arranged as far as putting figures into the right places and keeping the dramatic action flowing without too much standing around going on. It doesn't however attempt to add anything to the comic situations that might enhance or even improve the weaknesses in Verdi's musical direction. The stage direction gets the balance right to the extent that it flows along wonderfully without it ever jarring in any way, taking you along with the flow, but it's not particularly adventurous and this opera could use an injection of a little more humour.

Fortunately, the singing is all-around terrific, giving as fine an account of the work as you could hope for. The younger singers come over best, Alessandra Maranelli's sweet sounding mezzo-soprano and Ivan Magri's strong but lyrical Edoardo working well together, finding a good balance between the Verdi sound and the Rossinian. The others however are just as good - Guido Loconsolo as Belfiore, Andrea Porta as Baron Kelbar, Anna Caterina Antonacci as the Marquise and Paolo Bordogna as La Rocca, all managing to bring a degree of character to their roles, singing well, working with each other and with the comic-timing of the piece.

Un giorno di regno is the second release in the 'Tutto Verdi' series from C-Major, a collection that is made up of performances of all Verdi's opera work recorded at the Teatro Regio di Parma. Some trailers for other works in the collection are included on the disc, as well as a visual introduction/synopsis for Un giorno di regno. The quality of the HD image and sound - in PCM Stereo and DTS HD-Master Audio 5.1 - is marvellous. The Blu-ray is all-region, with subtitles in Italian, English, German, French, Spanish, Chinese, Korean and Japanese.

Giuseppe Verdi - Oberto, Conte di San Bonifacio

Teatro Regio di Parma, 2007

Antonello Allemandi, Pier' Alli, Mariana Pentcheva, Fabio Sartori, Giovanni Battista Parodi, Francesca Sassu, Giorgia Bertagni

C-Major

Verdi's first opera, written when he was 26 years old, might lack the musical sophistication and dramatic characterisation of his late masterpieces, but Oberto, Conte di San Bonifacio was good enough to open at La Scala in Milan in 1839, where it enjoyed a modest success, and it's a prototypical full-blooded early Verdi work that already has many of the elements that we associate with the composer. There's a historical subject based around war and revolution and an arranged marriage - but it's not Don Carlos by any means - there's a young woman whose father is outraged that she has been seduced and abandoned by a rakish noble - even if it can't stand up alongside Rigoletto or Simon Boccanegra or any of the other Verdi operas that deal with the father/daughter relationship. Oberto rather sticks closely to the established format and subject matter of the 19th century Italian number opera, but Verdi's dramatic flair, his ability to underscore those key moments with the most stirring and passionate arrangements is evident nonetheless and those qualities are brought out exceptionally well this production.

There's not a lot of dramatic action as such in Oberto. Much of the important events have already taken place, leaving the principal characters involved to fume their displeasure and deep feelings of love, betrayal, anger and desires for revenge at the start of the opera through a series of cavatinas and cabalettas. At the centre of the drama - like many of Verdi's works - is a father/daughter relationship that has been affected by war and revolution. Oberto, the Count of San Bonifacio, has been driven into exile, leaving behind his daughter Leonora. Leonora in his absence has been seduced by Riccardo of the Salingherra family - Oberto's sworn enemies - under a false identity. With Riccardo about to be married now to Cuniza, the sister of Ezzelino, an influential ally, Leonora bemoans her shame and Riccardo's betrayal. Her father Oberto however has secretly returned and incensed by what has happened, he urges his daughter to go speak to Cuniza and avenge her honour, turning up before the wedding to resolve the matter himself in the traditional fashion of a duel. It's pretty standard plotting then, the drama driven by a series of arias/cabalettas, but Verdi brilliantly whips this up into something utterly compelling by adding trios, quartets and choruses to create an explosive atmosphere in manner that makes it impossible not to get swept along.

Recorded in the small, intimate surroundings of the Teatro Verdi di Busseto, this 2007 production settles for a relatively traditional setting that has an appropriately theatrical feel to it. There's nothing too ambitious attempted, the costumes are theatrically period, the sets are confined to backdrops, with minimal use of props and the stage - small as it is - left clear and open for the singers to step forward and let fly. In the absence of any real dramatic interaction, the director Pier' Alli merely gets the performers to stand looking out, look sincere, strike a few dramatic poses and make some curious sweeps of the arms and hand gestures. The presumption - a big one possibly for what is after all Verdi's first opera - is that the music and singing alone will be enough to carry the full force of the work. Fortunately, while it's not left to rest entirely on the shoulders of the performances - the lighting and setting providing an effective and appropriate mood for the work - this turns out not to be an entirely unreasonable assumption.

The singing is generally good, but in such a stripped down production and with the musical arrangements as they are, there's nowhere to hide any weaknesses. There are no concerns at all however with the male tenor and baritone roles. Fabio Sartori gives a gutsy performance as Riccardo, pitching his performance perfectly for the tone of the work and the scale of the theatre, while Giovanni Battista Parodi's Oberto is similarly well-judged, striking the right note as the outraged father looking to restore his dignity without taking it overboard. Mariana Pentcheva also gives a performance of dramatic intensity as the deceived bride-to-be Cuniza, and it's only Francesca Sassu's Leonora that shows any real weakness in the line-up. The merciless acoustics of the small theatre and the opera's musical arrangements will quickly reveal any weaknesses, and in this context Sassu sounds unable to bring any depth or drama to the lower end in her opening cavatina, but also fails to hold her own in her Act I duet with Parodi.

When fully supported however, as the opera gathers pace with Verdi works up the musical drama and lightning effects are thrown in for good measure, the qualities of the work and the production become clear. The trio at the revelation of Riccardo's betrayal - resounding with Oberto, Leonora and Cuniza cries of 'traditor!' - is the highlight of Act I, Verdi following it up impressively with a powerful finale, while Act II's quartet has much the same impact, achieving the full Verdi effect. The chorus have an important part to play in this, and do so marvellously, but the main part of the success of this production rests on the driven performance of the orchestra as conducted by Antonello Allemandi that is nicely attuned to the rhythms and dynamic of the work. The sound quality on the Blu-ray disc is simply outstanding. Every instrument is crystal clear, highlighting just how good an account of the work this is.

Released on Blu-ray by C-Major, the image quality every bit as good as the HD sound mixes, Oberto is the first of a series of performances recorded at the Teatro Regio di Parma that will form part of a complete Verdi collection, 'Tutto Verdi', released to coincide with the composer's bicentenary in 2013. Some trailers for other works in the collection are included on the disc, as well as a visual introduction/synopsis for Oberto. The Blu-ray is all-region, with subtitles in Italian, English, German, French, Spanish, Chinese, Korean and Japanese.

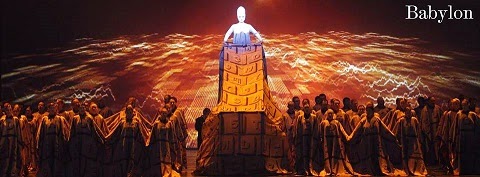

Jörg Widmann - Babylon

Bayerische Staatsoper, Munich, 2012

Kent Nagano, Carlus Padrissa, La Fura dels Baus, Claron McFadden, Anna Prohaska, Jussi Myllys, Willard White, Gabriele Schnaut, Kai Wessel, August Zirner

Internet Streaming, 3 November 2012

The first opera for the new 2012/13 season of the Bavarian State Opera in Munich was something of a bold statement of intent. A new modern opera receiving its world premiere, Babylon is an almost three-hour long epic with lavish production values that seem to fly in the face of European austerity measures and defy restraints on budgets in the arts. With a libretto written moreover by philosopher Peter Sloterdijk and music composed by Jörg Widmann, the 39 year old student of Hans Werner Henze, it seemed something of an omen that Henze should die mere hours before the opening performance, leaving the way for his protégé to make a mark on modern opera with an important new work. There was consequently a weight of expectation surrounding the opening of Babylon, and with a visually astonishing production from Carlus Padrissa of La Fura dels Baus that was perfectly in accord with the colourful nature of the work, the opera certainly made an impression, even if its impact was inevitably somewhat reduced for those watching it (and experiencing technical difficulties) with its Live Internet Streaming broadcast on the 3rd November.

Babylon relates back to Biblical times and ancient Mesopotamian mythology, to human sacrifice practiced by the Babylonians and the repudiation of it by the Jews, to the destruction of the walls of Jericho and the founding of urban civilisation. Central to the work then, with its invocations of the mystical number seven, is the formation of order out of chaos, an order associated with numerology that is reflected in the establishment of the seven days of the week. It's a love story that is both the cause of the chaos that ensues as well as what brings about redemption and order. Widmann's opera opens then with a prologue showing a scene of apocalyptic devastation, a scorpion man walking through the ruins, before the Soul arrives to open up the first of the opera's seven scenes, mourning the loss of Tammu, a Jewish exile living in Babylon who has fallen in love with Inanna, a Babylonian priestess in the Temple of Free Love.

The visions of chaos and destruction continue unabated as Tammu lies with Inanna, and is awoken through love and some herbal induced visions - the seven planets and even the Euphrates itself bearing testimony - to the truth that their world is founded on chaos that the Gods have unleashed upon the universe. (Mozart and Schikaneder's The Magic Flute is obviously drawn from the same sources - Tamino and Pamina recognisably relating to Tammu and Inanna). It's this chaos that the Babylonians hold at bay through human sacrifice, a "truth" that is hidden by Ezekiel in his teachings of the Jewish law and the stories of Noah and the flood. When Tammu is chosen as the next human sacrifice however and is executed by the High Priest following the New Year celebrations, Inanna joins with the Soul in her lament for his loss. Inanna pleads with Death to allow her to journey to the Underworld to bring Tammu back.

Undoubtedly the most striking thing about Babylon is the direction of this vast undertaking by Carlus Padrissa of La Fura dels Baus, with its spectacular production designs by Roland Olbeter. Every element of the ambitious libretto, with all its mystical symbolism, dreams, visions and mythology, is presented in visual terms that aren't merely literal, but connect on an intimate level with the music and the concepts wrapped up within it. In its seven scenes (with a prologue and an epilogue) a Tower of Babel is erected and destroyed, the seven planets appear during Tammu's visions, the River Euphrates is personified as well as represented by a stream of words and letters that flood and overflow, seven phalluses and vulvas appear with seven apes during the New Year celebrations, flaming curtains give way to sudden downpours during the sacrifice of Tammu, and Innana wades through a seething mass of (projected) bodies, discarding seven garments (a dance of the seven veils), as she journeys into the Underworld. The stage is never static, there's an incredible amount going on, with extraordinary detail in background projections, processions, with supernumeraries in all manner of costumes and guises.

Babylon is therefore, opera in its purest sense. The music and singing alone don't stand up on their own, the spectacle alone isn't enough, but the work needs each of the elements of the libretto, the music, the performance and the theatrical presentation to work together and in accord to put across everything that is ambitiously covered in the work. Widmann perhaps takes on too much across its great expanse of scenes and musical styles - cutting suddenly between twelve-tone dodecaphony, jazz, cabaret and Romanticism - to the extent that it can feel episodic and difficult to take in as an integral and consistent work. Babylon however has a solid foundation in its subject, in Kent Nagano's marshalling and conducting of the orchestra of the Bayerische Staatsoper, in Padrissa's impressive command of the visual elements, and in Anna Prohaska's extraordinary performance as Innana that goes beyond singing. Babylon is opera in the purest sense also in that it undoubtedly needs to be experienced in a live theatrical context in order for its full power to be conveyed. On a small screen, viewed via internet streaming, the rich scope, scale and ambition of the work were nonetheless clearly evident.

Giacomo Puccini - La Bohème

Den Norske Opera, Oslo, 2012

Eivind Gullberg Jensen, Stefan Herheim, Diego Torre, Vasilij Ladjuk, Marita Sølberg, Jennifer Rowley, Giovanni Battista Parodi, Espen Langvik, Svein Erik Sagbråten, Teodor Benno Vaage

Electric Picture

The first notes you hear in this 2012 Den Norske Opera production of Puccini's La Bohème are the beeps of a heart monitor on a life support system that Mimi lies attached to in a hospital bed. The beeps take that familiar flatline tone as Mimi breathes her last and doctors rush in to the opening chords of the score proper in a vain attempt to resuscitate her, while Rodolfo looks on aghast, completely lost in his own grief. This evidently isn't a traditional way to start La Bohème, but it is very much a typical Stefan Herheim touch where the standard linear approach is just not an option. As a director, Herheim is clearly interested in getting into the minds of characters whose actions and motivations we can take for granted from over-familiarity, and La Bohème is a very familiar opera. Not here it isn't.

Having established that Mimi dies - which, let's face it, even if you weren't familiar with the opera, it's a fate that is signalled clearly enough by Puccini right from the moment she totters and stumbles into Rodolfo's garret, often with a hefty tubercular cough for good measure - Herheim is more interested in the impact her death has on Rodolfo after the opera ends, considering the times and the troubles they have shared together. Here then, viewed in flashback, La Bohème becomes a study of grief and bereavement that Rodolfo struggles to work through and eventually come to an acceptance of his loss through his poetry and his friends. If anyone can make such an idea work, working within the fabric of Puccini's scoring without necessarily contradicting sentiments that are implicitly there in the nature of the music itself, it's Herheim. Whether you think there's any value in distorting the work to that extent is of course debatable, but there is certainly more intelligence in this thoughtful and considered approach than your average straight production that merely "performs" the work, Herheim taking into account the very real emotions and troubles of characters whose lives are played out in art and poverty. It's certainly at least a refreshing alternative for anyone who is more than familiar with the long-running Copley and Miller productions of the work at the Royal Opera House and the Coliseum in London.

His grief played out in flashback then, the past and the present coexist simultaneously for Rodolfo, who has no means of pulling them together. The hospital ward seen at the start then opens up to a more traditional view of the past in Rodolfo's Parisian garret where he and Mimi first met, the cleaner, surgeon and nurse taking up roles as the other characters (introducing Musetta into the process rather earlier too). The sense of perspective however shifts in a subtle way to tinge the meeting with that sense of grief for the inevitability of what has happened/will happen. When Rodolfo poses the question 'Qui sono?' to himself here then - looking thoroughly confused - it takes on an entirely different meaning, one that involves real soul-searching, as well as a certain existential dilemma. Compressing and overlapping time in this way simultaneously concentrates all the joy and happiness of that fleeting moment of beauty, while forcing one to consider how brief and vulnerable are the flames of love on those candles that are so soon to burn out. The same flames of love will burn Rodolfo as well as provide warmth through the winter. Rather than contradict the emotions of a beautiful piece (Act 1 of La Bohème is for me something incredibly powerful), this production genuinely enhances what is already there.

There are lots of touches however that aren't going to be to everyone's liking. Already in this First Act, Mimi collapses, her wig is removed to reveal a bald head that bears the signs of chemotherapy (this Mimi is dying from the rather more contemporary killer of cancer rather than the traditional old-fashioned disease of tuberculosis), and she is ushered back into that modern hospital bed that looms at the corner of Rodolfo's consciousness. The shifting of the off-kilter sets from one 'reality' to the next - incredibly well designed to transform so smoothly - have an unsettling effect not only on Rodolfo but on the viewer also, leaving them unsure at times about what exactly is going on, and why the familiar figures in the work don't behave in character in the way that we expect. Mimi "dies" again at the end of Act II, for example, and her medical chart is added to the Café Momus "bill" that has to be paid at the end. I think the implication is clear enough. Unwilling to "pay the bill" however the near-demented Rodolfo here is so impassioned that you get the impression he believes he could bring her ghost back to life by the end of the opera. Wouldn't that be something? But no, Herheim stays faithful to the intentions of the work. "Per richiamarla in vita non basta amore" - "Love alone will not suffice to bring her back to life", he says in Act III. It's all there in the libretto if you want to look for it.

The absurd modern twists on an otherwise faithful staging can be a little off-putting - or will be simply intolerable to some viewers - but they can also be extremely powerful. If you consider that Puccini's writing here is extremely manipulative and has a tendency towards heavy pathos, sentimentality and schmaltz, Herheim's staging forces you to listen to the music in a different context, and the effect is phenomenal. Puccini, like the listener, knows Mimi's fate from the outset, and doesn't pretend otherwise. The tragedy isn't so much that Rodolfo doesn't know it, or that he is unwilling to face up to her flirtatious and mercenary nature, or even the realisation that she's seriously ill and going to die, but rather, that he is on some level aware of it, but still loves her despite it all. All those implications are there in Puccini's score and brought out in the development of the opera if you want to explore them, and Herheim does. Using Rodolfo's inability to come to terms with his grief as a means of showing his struggle to deal with the inevitability of what must occur not only makes this almost indescribably sad, it's also an effective way of dealing with some of the problematic issues surrounding Puccini's generously expressive scoring.

Aside from the technicalities and impressions created by Herheim's direction and Heike Scheele's set designs, the performance of the work itself is overall very good. The added dramatic twists moreover rather than getting in the way of the performances only seemed to intensify their impassioned delivery. More so Rodolfo than Mimi, it has to be said, Diego Torre singing the role superbly, with consideration for the different nuances of meaning applied to his character. By focussing the attention on Rodolfo's state of mind and resigning Mimi to little more than a ghost however, the consequence is that it weakens Marita Sølberg's contribution to the work, but she sings it well in the context. The subjective view of Rodolfo also has a consequence of reducing the relevance of the other characters to relatively minor roles, but even if it loses some of the contrasting elements of the nature of relationships that is brought out by the Marcello and Musetta pairing (adequately sung by Vasilij Ladjuk and Jennifer Rowley), the tightening of the focus isn't necessarily a bad thing in this work either. Svein Erik Sagbråten's recurring Death-like presence as the landlord Benoît, Parpignol, Alcindoro and a Toll gate keeper could also be seen as bringing more of a consistency to the colourful but marginal episodes of the work.

On Blu-ray, the production looks and sounds as good as you would expect from a recent HD recording. The singing sounds a little echoing in both the PCM Stereo and DTS HD-Master Audio 5.1 mixes, but I found that the stereo track sounded much clearer through headphones. The recording and mixing of the orchestra however is gorgeous, with lovely tone and detail in the orchestration. It's a good account of the work - Eivind Gullberg Jensen directing the opera for the first time - attuned to the performances and only slightly adjusted in one or two places for the tempo and tone to match the production. There are a few very short interviews on the disc (around a minute each) with the director, conductor and cast, done backstage in the intervals presumably during a television broadcast of the live performance. The BD is all-region, with subtitles in English, French, German, Spanish, Italian and Korean.