Ambroise Thomas - Hamlet

Buxton International Festival, 2025

Adrian Kelly, Jack Furness, Alastair Miles, Allison Cook, Gregory Feldmann, Richard Woodall, Yewon Han, Joshua Baxter, Tylor Lamani, Dan D’Souza, Per Bach Nissen, John Ieuan Jones, James Liu

Buxton Opera House, 22nd July 2025

Adapting Shakespeare's Hamlet as a grand opéra would necessarily have imposed certain conventions that could only work against the dramatic flow of the play, not to mention the surely unacceptable requirement to rewrite the play's bleak conclusion, so you can't really fault Ambroise Thomas then for the approach he takes. I doubt that even Verdi, a contemporary of the French composer, would have done it much differently since his own versions of Shakespeare take similar necessary liberties with the plot and characterisation to fit with the conventions of the opera form. Well, he might not have included three (not just one, not just two, but three! Or at least two and a half) grand opéra drinking songs, but you can't fault Thomas for excess when it comes to this particular work. To state the obvious, there is a lot of drama in Hamlet.

And death. A lot of dark drama, death, madness, vengeance (you almost wish Verdi had given it a go on that basis, but we have Macbeth and Otello, not to mention Falstaff, and those are all great in their own way) and, drinking songs notwithstanding, that's the ominous tone that rightly dominates in Thomas's Hamlet. Correspondingly, that's the tone that is established in the 2025 Buxton International Festival production directed by Jack Furness and conducted by Adrian Kelly. It's dark, dramatic in voices, ominous in the music, dynamic in its performance, matching the pent up anger of the production's Hamlet, Gregory Feldmann, who paces the stage like a tiger, raging out self-absorbed soliloquies. It maintains this mood so effectively that it comes as no surprise then when we come to the Act IV, we find that Thomas has composed not just a mad scene for Ophelia, but a whole mad Act.

But there are genuine valid reasons for such excess of emotion in Hamlet. Perhaps Thomas's lyrical score and the truncated French language libretto shorn of the original's poetry don't get to the heart of the many factors that contribute to its depth of expression, but the music although romanticised is dramatically attuned. What it needs to work on stage (and rarely achieves in my experience) is a director who is prepared to delve into what remain contemporary and relevant themes in the play that are not fully exploited in the opera version. Jack Furness does just that in a direct and simple way without over-imposition. One of the many themes that can be drawn out of Hamlet for greater attention is the subject of what it is like to live under surveillance in a corrupt, self serving and authoritarian state and the impact this has on society. If there is any theme that is more relevant to the world (and the UK) today, a way that lets us see deep into the heart of the drama of Hamlet and see the changes happening in our contemporary world reflected back at us, it's this.

This is handled well by the director with simple side touches that don't impose on the dramatic content of the opera, but rather give it depth and context. We get a hint of it right at the beginning of the production when a lone protestor runs to the front of the stage during the wedding of the new king Claudius to his dead brother's wife Gertrude with a poster that suggests 'No Kings' or 'Not My King'. He is quickly bundled off stage by heavily armed militia who continue to carry out brutal arrests and beatings in the musical interludes between acts. At the beginning of the final act a hooded woman is led across the stage, knelt down and summarily shot in the back of the head to the shock of the audience.

Where this is relevant is in how it feeds into Hamlet's behaviour. With such state oppression and killing of civilians going on in the background, his fury at the man who he believes has killed and taken the place of his own father is compounded by his inability to translate that righteous anger into action and prevent such wider crimes against the populace. You can feel that in every scene; it's not self-pitying grief but self-questioning doubt. Hamlet rages impotently and hates himself for it, retreating into madness. In that context, the original 'happy ending' composed by Thomas which hurtles in there with no warning, works really well here. Or is made to do so by Jack Furness in the Buxton production.

Thomas's original ending sees Hamlet alive and crowned king, but since it wasn't felt that this twist would be accepted in Shakespeare's own country, it had to be reworked for the opera's London premiere a year later in 1869. Not that Hamlet expiring over the dead body of Ophelia in the final scene is any truer to Shakespeare, but letting Hamlet live and become ruler opens up more questions that it resolves. Here, since the director has laid the groundwork for what a corrupt ruler has done to his people, Hamlet knows that action is needed; the voices of the dead tell him. He knows also that he can't just unleash chaos and leave it for someone potentially worse to come along, but needs to own it. Even Shakespeare's play, although it ends on a completely different note, nonetheless has a similar message that Hamlet's story must serve as an example to others.

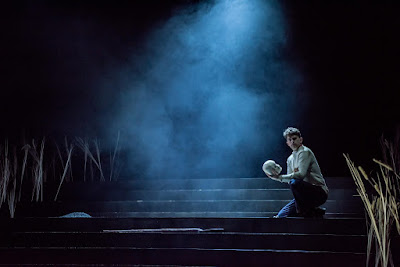

What also helped the opera work so well in the Buxton International Festival production was a balanced restraint in the set designs and presentation. For the most part the drama takes place on narrow platforms on a wide staircase. It looked like Sami Fendall's set designs would be inadequate for such an epic drama but - a little like Olivier Py's production of this opera - it recognises that the real drama in Hamlet is an interior struggle. As such, Jake Wiltshire's hugely effective lighting and swirling mists provided a great deal of support to make Thomas's score feel much more ominous than it might have otherwise. There were however additional touches where required; a slatted wall a cage where Hamlet prowled like a tiger unable to pounce on his vulnerable uncle, and the riverbank scene for Ophelia; both scenes simple but effective. The underlying menace was ever present in the US ICE-like immigration military troops maintaining order by rounding up protestors and troublemakers.

Conducted by Buxton's musical director Adrian Kelly, the festival orchestra gave a balanced reading of the score with no inappropriate Verdi-like bursts of thunder. Instead, the flowing melodies and the dramatic accompaniment of the score were allowed to work within the context of the stage production to achieve the necessary impact. Best of all was the singing. There was well-deserved acclaim for Yewon Han's Ophélie. She very much has a key role in the opera and not just a scene stealing role despite being written to appeal to a French audience in thrall to the character, but here the role was dramatically coherent and, as sung by Yewon Han, vocally effective. Allison Cook was excellent as Gertrude. Often the victim of Hamlet's anger and abuse, she rose to the challenge of the role and you really felt Gertrude's conflicted position. Alastair Miles is still one of the best bass singers in the UK and was outstanding as Claudius. Gregory Feldmann's intensely delivered soliloquies as Hamlet were met with surprising silence during the performance. That was more of an indication that they were too raw, too real, and it seemed rude to intrude upon his grief with applause that would have broken the spell. At the curtain call however he received and deserved every plaudit and cheer.

I haven't had a lot of time for Thomas's Hamlet up to now, but to be fair it is not performed that often and as an opera it has to compete with one of the greatest plays in the English language, in French moreover and in a grand opéra format, so the challenges are considerable. The production I saw in Strasbourg in 2011 appeared to have been heavily cut and seemed to me disjointed and I couldn't get past what had been done to Shakespeare's poetry and dramatic drive, As an actor himself, Olivier Py showed that there was considerably more you could do with the work in his 2014 production for at La Monnaie in Brussels, but Jack Furness and Buxton have proved again that neglected works with perceived flaws can have those weaknesses turned into strengths. What they do here in opera terms is what any dramatic presentation should do when confronted with a complex work like Hamlet, which is make it feel vital, relevant and relatable. And any production of Hamlet whether theatrical or operatic should have you gripped, shocked and impressed, and this superb production at Buxton did just that.

External links: Buxton International Festival