Charles Gounod - Faust

Charles Gounod - Faust

Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, 2011

Evelino

Pidò, David McVicar, Vittorio Grigolo, René Pape, Angela Gheorghiu,

Dmitri Hvorostovsky, Michèle Losier, Daniel Grice, Carole Wilson

Live

HD Broadcast, 28th September 2011

It’s not too difficult to see why Faust

is considered one of the jewels of French grand opera, nor why,

featuring as it does in no less than three opera houses in my viewing

schedule this quarter up to Christmas (Covent Garden followed by the

Paris Opéra and the Met in New York), it still remains a popular fixture

in the repertoire of many major opera houses around the world. With a

tragic love-story, whose content is boosted somewhat with a cruel

encounter between evil and innocence, all wrapped up in a sense of

religious fervour, the purpose of the storyline might deviate from the

original intentions of Goethe’s classic tale, but it has all the right

elements for a passionate opera subject.

The storyline however is actually the least convincing thing about Faust,

but the emotional range covered across those Manichean divisons provide

Charles Gounod with everything he needs to spin it out into a wonderful

variety of musical arrangements. It opens with the aged scholar Faust

despairing and disenchanted with a life devoted to study that has failed

nonetheless to provide any great revelations or even meaning. Given

the chance by the demon Méphistophélès to seek the pleasures elsewhere,

it’s a vision of a beautiful young woman, Marguerite, that convinces

Faust to enter into a bargain that will mean the loss of his eternal

soul. The dark, nihilistic tone of the opening – the first word spoken

by Faust is a bleak utterance of “Rien”, “Nothing” – gives way to

a sense of joyous hedonism, conquest and seduction that stands in stark

contrast to the daily lives and modest passions of ordinary people and

soldiers going to war. By the end of the opera, each of those

characters is judged for their actions.

Within that not particular

complex or surprising storyline where, of course, virtue is rewarded,

there is nonetheless a wealth of tones, moods, emotions and tempos, and

Gounod gathers them together with the all the most wonderful

arrangements available to a composer of grand opera. Filled with

memorable tunes and famous arias, including Marguerite’s famous Jewel

Song, Faust also contains a fabulous waltz, rousing marches,

numerous choruses and a ballet – all of which never fail to sweep up the

audience and get feet tapping. And if that’s the simple measure by

which you judge any performance of Faust, David McVicar’s

production for the Royal Opera House, with the superb playing of house

orchestra under conductor Evelino Pidò, broadcast live in High

Definition to cinemas across the UK and the world, was unquestionably a

success.

I’ve never been particularly

taken with David McVicar productions, failing to see much in the way of a

convincing concept or even a personal touch in his style other than it

usually being a hotchpotch of random and generic opera theatrics.

That’s the case here with his production of Faust, but it’s a

style that works quite well with this particular opera. There might be

little to distinguish the all-purpose set, but with a couple of

adjustments and a change of lighting it’s able to switch very

effectively between a scholar’s study and a church with an organ or

between a street-scene and a night-club cabaret. Even the random

elements in the wings – the opera house boxes on the left, the pulpit on

the right – provide space for nice little touches and coups de théâtre

on a stage where there is always something interesting going on. The

Act IV Walpurgis Night ballet was undoubtedly one of the high points of

the staging, but McVicar’s one little perverse touch in this opera of

having Méphistophélès dress as a woman in the scene where he shows Faust

the queens of the world actually worked quite well. I would never have

thought anyone could get away with putting René Pape in a dress and

tiara, but it actually suits the nature of his character here perfectly.

The big selling-point for this

particular production however is its top-flight cast that in addition to

Pape as Méphistophélès, has Vittorio Grigolo as Faust, Angela Gheorgieu

as Marguerite and Dmitri Hvorostovsky as Valentin. If none of them are

distinguished actors, you really couldn’t fault their singing. Each

and every highpoint for their characters was reached and in most cases

even surpassed. Grigolo started off slowly as the aging Faust, but more

than came into his role as the younger rakish seductor (as he did when I

last saw him in last year’s TV production of Rigoletto) while Pape, wearing a string of fine costumes was an appropriately magnetic and imposing presence in his demonic role.

Most impressive however was

Dmitri Hvorostovsky, who really put a heart and soul into Valentin with

an absolutely knock-out, spell-binding performance, but it was also

helped by McVicar’s strong direction of his scenes, using the character

for additional impact. Surprisingly, it was only the diva Angela

Gheorghiu, who really failed to shine. She sang perfectly well, if

somewhat underpowered in the role of Marguerite (a consequence perhaps

of the cold that saw last Saturday’s live radio broadcast replaced by a

recording?), but failed to find the right level to pitch an admittedly

difficult character. Sometimes however, it’s difficult to differentiate

whether she’s wrapped up in her character or just wrapped up in

herself. All in all however, this was a fine production of Gounod’s

classic, well up to the exceptionally high standards we’ve come to

expect from the Royal Opera House.

Giacomo Puccini - Turandot

Giacomo Puccini - Turandot

Arena di Verona 2010

Giuliano

Carella, Franco Zeffirelli, Maria Guleghina, Carlo Bosi, Luiz-Ottavio

Faria, Salvatore Licitra, Tamar Iveri, Leonardo Lòpez Linares, Gianluca

Bocchino, Saverio Fiore, Giuliano Pelizon, Angel Harkatz Kaufman

BelAir Classiques

It’s not as if there is a gap in the market for yet another performance of Turandot,

with there being a few versions already out on Blu-ray, and even one

that uses the same Franco Zeffirelli production recorded here at the

Arena di Verona in 2010. Taking advantage perhaps of Decca’s recall of

their Zeffirelli production of Turandot at the Metropolitan

Opera in New York due to a fault with the English subtitles, BelAir’s

release is a timely one that comes out in the gap before the Met

reissue. There’s certainly room in anyone’s collection for another

version of Puccini’s final masterpiece, but perhaps not yet another one

of this production.

Recorded at the huge stage in

the Roman arena at Verona at least gives Zeffirelli quite a bit more

scope and an impressive location for the sumptuous sets for this

fairy-tale opera. The Met production isn’t exactly understated, but here

at Verona, the director can at least double the number of

supernumeraries, have room for acrobatics and Chinese parade dragons,

but bigger doesn’t necessarily mean better (although try telling Franco

Zeffirelli that!). Attempting to fill the stage with people could be

seen as making things a little more cluttered, but – provided you don’t

have an aversion to Zeffirelli glittery gold extravagance – it does at

least give sets like the Royal Palace an appropriate sense of grandeur.

Where there’s room for

improvement over the Met version of this classic production – not much,

as it’s very good, but just a little in one or two areas – is in the

singing. Blow for blow however, there’s not much to choose between the

two casts other than personal taste and, perhaps more significantly, the

impact of the acoustics on the respective recordings. Maria Guleghina

is Turandot on both versions, and here – whether it’s through trying to

project to a bigger arena, I’m not sure – she sounds a little shrill and

strained in her riddle duel with Calaf, but she’s not perfect on the

Met recording either. She does however come through with great regal

presence and drama towards the conclusion. Tamar Ivéri sings Liù very

well indeed, and I’d be happy with her performance if I didn’t still

have Marina Poplavskaya’s deeply emotional performance and unique tone

fresh in my mind. Salvatore Licitra is a fine Calaf, but his voice

doesn’t always carry and he certainly doesn’t sustain his high notes on

Nessun Dorma, although he gives it another worthy effort in an encore

(this is Verona and the principal aim is one of popular crowd-pleasing),

but he performs reasonably well considering the challenges of the

outdoor arena setting.

Ultimately, it’s the occasion

and the acoustics of the Arena di Verona that make the difference here

at least as far as the singing is concerned. The acting is perhaps

turned up a notch to project to the arena and performers all make use of

discreet microphones, which means that it doesn’t consequently have the

same natural ambience of a traditional theatrical production. If the

Met production has the edge then in this regard, the Verona recording

has other aspects to recommend. The setting and the occasion are

impressive alone, but the performance of the orchestra under Giuliano

Carella is also noteworthy and has great presence in both the LPCM

Stereo and the DTS HD-Master Audio 7.1 sound mixes.

In all other respects, the same

qualities that can be found in the Met’s production also work here. The

settings and arrangements fully capture the fairy-tale scale of the

opera, but the direction sensitively brings out an appropriate sense of

the nature of the characters as expressed though the libretto and in

what Turandot’s riddles tell us about the respective personalities

involved and how love arises from them. Most importantly, Zeffirelli’s

production is perfectly in accordance with the tone of Puccini’s

fascinating Oriental-inflected score, and the sense of occasion that the

Arena di Verona lends it.

The quality of the Blu-ray

release from BelAir is quite good, through not perfect. There is good

detail in the image and strong colouration that captures the full glory

of the production, but the encoding isn’t the best and movements aren’t

the smoothest. This will probably vary according to individual systems

however. The audio mixes in LPCM and DTS HD-Master Audio 7.1 are both

good, allowing finer detail to be heard in the orchestral the

arrangements, and covering the singing reasonably well considering the

acoustics and use of attached mics. I didn’t however particularly note

any extra dynamic on the surround mix. There are no extra features on

the disc, and only a detailed synopsis and credits in the enclosed

booklet.

Georg Friedrich Handel - Alcina

Wiener Staatsoper, Vienna 2011

Adrian

Noble, Marc Minkowski, Les Musiciens du Louvre-Grenoble, Anja Harteros,

Vesselina Kasarova, Veronica Cangemi, Kristina Hammarström, Alois

Mühlbacher, Benjamin Bruns, Adam Plachetka

Arthaus Blu-ray

If it doesn’t do the mostly

static and uneventful nature of Handel’s 1735 opera any favours, it’s at

least appropriate that director Adrian Noble chooses to stage this

production for the Weiner Staatsoper entirely within the ballroom of a

stately house. Alcina does indeed feel small and intimate – some

might say dry and mechanical – the kind of entertainment put on for the

amusement of a gathering of nobles at an 18th century dinner party.

That’s not exactly high-concept, but it’s about as adventurous as you’re

going to get for a rare performance of a Baroque opera at the Vienna

Staatsoper (the first in 50 years), and if it doesn’t do much for the

opening up of Alcina, it at least recognises its limitations and,

under the baton of the excellent Marc Minkowski, it’s about as good an

account of the opera as you could expect.

The play within a play concept

is only really nominally adhered to, the overture used to set the

occasion within Devonshire House, where Georgiana Cavendish, Duchess of

Devonshire and some guests (you would only know this from the production

notes) put on a performance that perhaps appeals to or reflects their

nature. The Duchess becomes the sorceress Alcina, who enchants men and

then casts them off, changing them into wild beasts, trees or ghosts,

left to roam her island. Her latest conquest is Ruggiero, who is

unaware of his fate, but when his betrothed Bradamante (disguised as a

man, Ricciardo) and Melisso, her tutor, come to rescue him, Alcina

recognises that she may indeed have real feelings for him. There’s not a

whole lot more to the opera than this. There are a few additional

complications added with Alcina’s sister Morgana falling in love with

Ricciardo (not realising he is actually Bradamante), which enrages

Oronte, Alcina’s general who is in love with her. There’s another

figure, Oberto, taken in after he and his father were shipwrecked on the

island (his father since turned into a wild beast). And just in case

that’s all not confusing enough, there are the usual identity problems

with trouser roles to come to terms with. Not only is the young boy

Oberto played by a female, but Ruggiero is a woman playing a male role

who is betrothed to a woman dressed as a man.

That’s complicated enough to

get your head around without having to consider that Adrian Noble’s

production has historical figures playing these roles, but it’s not as

complex as it sounds. The dramatic action is limited and the emotional

content isn’t that deep, the endless da capo arias expressing no

profound wisdom or inner turmoil and no noble sentiments beyond simple

expressions of love, rejection and love again, repetitively back and

forth as awareness of identities and natures are revealed. Essentially,

it’s a case of the power of true love prevailing. Handel’s Italian

operas can be rather dramatically limited in this respect – certainly

when compared to his oratorios – and Alcina seems relatively

straightforward in its playing out of the situation, with arrangements

that aren’t particular complex. Mood and character however are

tastefully evoked throughout, but there are indeed also some beautiful

heart-rending arias and melodies by the time the characters reach the

crux of their situation at the end of Act II and in Act III.

If the staging is slightly

static in an opera where nothing much happens – a fact only emphasised

by non-participant guests sitting around watching the performance –

Adrian Noble at least makes it all look very lovely indeed, with

striking lighting, colours and simple effects that are appropriate to

the occasion but highly effective. The tone is matched by Minkowski’s

conducting of the Musiciens du Louvre-Grenoble, finding the rhythmic

centre of the score, the whole ensemble bright, vivid and dynamic, but

with a delicate touch to individual instruments which are picked out

beautifully in the sound mix. The single greatest thing about the

choice of staging however is indeed the use of a small core of musicians

on the stage creating a wonderful connection in their accompaniment of

the singers.

The most notable singing here

is from Bulgarian mezzo-soprano Vesselina Kasarova as Ruggiero,

demonstrating a remarkable range from deep notes to high coloratura

seemingly effortlessly. Her delivery and acting can be slightly

mannered and even distracting, perhaps on account of playing a male

role, but I don’t think the Vienna audience give her the credit she

deserves here. Kristina Hammarströmn is a good Bradamante and Anja

Harteros fine as Alcina, if a little lacking in character. There are a

few off-notes here and there, but her Act II aria “Ah! Mio cor! Schernito sei!”

is one of several beautiful Handel compositions here and sung very

well. As Oberto, Alois Mühlbacher thankfully adds some variety to the

voices and the repetitive romantic declarations and expressions of

disappointment in rejection.

Drawn out to three and a half-hours, those sentiments can become rather tedious after a while, but while Alcina

isn’t the greatest Handel opera and is fairly static and limited in its

dramatic situation, its overall construction is carefully considered

and it’s worth persevering with for the some wonderful moments and

beautiful arrangements that arise out of it as a whole. The staging and

performances from the orchestra and the singers all ensure that those

qualities come through.

As do the specifications of

the Blu-ray from Arthaus. The sumptuous staging is finely detailed and

extraordinarily colourful and, other than the use of fades and one lapse

of rapid cross-cutting, the filming is fine. The PCM stereo and the

DTS HD-Master Audio mixes are impressive. Subtitles are in Italian,

English, German, French, Spanish, Japanese and Korean. A twenty-minute

behind-the-scenes featurette is included.

Giuseppe Verdi - Les Vêpres Siciliennes

De Nederlandse Opera, Amsterdam 2010

Paolo

Carignani, Christof Loy, Barbara Haveman, Burkhard Fritz, Alejandro

Marco-Buhrmester, Bálint Szabó, Jeremy White, Christophe Fel, Lívia

Ághová, Fabrice Farina, Hubert Francis, Roger Smeets, Rudi de Vries

Opus Arte

In the behind-the-scenes

featurette on the BD for this opera, Frank, one of the nearly 100 strong

chorus of the Nederlandse Opera, says that he feels like he is not just

one of the crowd in this production, he’s part of history. And in a

way, there is definitely something momentous about Verdi’s Les Vêpres Siciliennes

(1855). It’s not just the fact that it’s Verdi in full-blown Grand

Opéra mode, in French moreover, or that it’s based around an historical

event that has contemporary and political significance for the

revolutionary-minded composer himself – but it’s also a lesser-known

Verdi opera, very rarely performed or recorded, even more rarely in its

full French version complete with a half-hour ballet in the middle. The

Dutch production of Les Vêpres Siciliennes in Amsterdam is certainly an historic occasion then, and what a fascinating, thrilling and momentous event it turns out to be.

The original historical events

referred to in the opera date back to 1282, when the Sicilian people

rose up against the cruel French occupying forces after one outrage too

many committed against the ordinary citizens. You would imagine that

Verdi was less interested in the historical Vespri Siciliani than he was

about the revolution in Italy in his own time, and stage director

Christof Loy likewise isn’t concerned about setting this production of

the opera to any specific historical time period. Nominally however,

it’s set in the 1960s (the dates of birth of the young protagonists are

given as the early 1940s), which would seem to draw a parallel with

events in French-occupied Algeria, but there is nothing culturally

specific that makes any reference to this. Loy’s direction then is by no

means the fiasco that has been suggested elsewhere.

The director’s

touches are distinctive certainly, and not for everyone, but taking the

opera out of its natural time period – which would have no meaning or

significance for a modern audience anyway and arouse none of the

passions Verdi undoubtedly was aiming for – Loy manages nonetheless not

only to do great service to the opera and even help cover over some of

its flaws.

The staging has much of the same look as Loy’s Salzburg production of Handel’s Theodora,

and it has a very loose thematic connection in it being about citizens

standing up to the abuse of a foreign power. Similarly, the sets are

kept minimal, with rarely anything more than a few chairs scattered

around the stage, creating a sense of timelessness that is reflected in

the costumes. The French, like the Romans in Theodora, for the most part

wear formal dinner jackets, the Sicilians casual jeans and shirts, with

only Hélène – the Duchess – wearing a man’s suit and tie. The political

and social distinctions are therefore much more meaningful to a modern

audience than any period costumes. Props and effects are rarely used,

but when they are (bottles and glasses, slides and projections) they are

employed to good effect and for maximum impact. The main part of the

Loy’s work however is in his directing of the singers, their movements,

placement and their interaction, and it’s hard to see him putting a foot

wrong anywhere in this respect, as the full impact of the complex

relations between the characters, their backgrounds and motivations all

come through.

Where the plot and the libretto

are less convincing, Verdi music fills in the gaps and Loy steps back

and lets it speak for itself (the otherwise static Act IV for example is

powerful simply through a magnificent set of duets, trio and quartet).

In the places where even Verdi’s judgement of the occasion is

questionable – the start of Act V for example, Loy steps in and manages

to make something more meaningful out of it. The director chooses the

Four Seasons ballet in Act III to be the thematic centrepoint of his

interpretation (controversially it would seem), giving motivation to

Henri’s later actions that are otherwise difficult to reconcile, the

revelations about his own origins and his father leading him to idealise

or just imagine how things might have been different. This illusory

ideal leads him to believe that his marriage to Hélène at the start of

Act V (the same fantasy home setting of the ballet is used here) –

otherwise an improbably joyous occasion considering the circumstances –

could bring a true peaceful union between France and Sicily. It’s a

thoughtful interpretation by a director who clearly cares enough to play

to the opera’s strengths and mitigate its weaknesses. At the very

least, it’s certainly preferable to simply cutting the ballet, as would

be more common (if the opera were indeed more commonly performed), and

letting it limp by with its inherent flaws.

Although there are some

unfamiliar elements, the opera itself is recognisably and

whole-heartedly Verdi, with romantic tragedy, dire threats of revenge

and rousing revolutionary sentiments. Musically, Les Vêpres Siciliennes doesn’t always feel like the Verdi we know, but, like Don Carlo

(a much better opera admittedly), there’s something fascinating and

appropriately dramatic about having the Verdi experience filtered

through the French Grand Opéra idiom, with its echoes of Un Ballo in Maschera and even Rigoletto and La Traviata

here, with its rousing choruses and its grand Overture (placed

strangely between Acts I and II here, but no less effectively), but with

unexpected delicacy and with musical arrangements that I’ve never heard

from Verdi before, such as in the wonderful ballet music. The orchestra

and the chorus, under Paolo Carignani, are outstanding in their

delivery, the opera approached with a real Verdian sweep.

The singing – even though there

are some difficult passages and coloratura to navigate right at the end

of a long opera – is for the most part beyond reproach. Barbara Haveman

is a great presence, the charismatic figure that Hélène needs to be,

her singing strong and heartfelt throughout. Burkhard Fritz is a lovely

lyrical tenor who manages to make the difficult nature of Henri’s plight

sympathetic. Bálint Szabó’s bass makes for a grave, dignified, yet

compelling revolutionary voice as Procida. Alejandro Marco-Buhrmester is

fine, but the weakest of the principals, not really cutting a strong

enough figure as Montfort, and his singing isn’t as clear and resonant

as the others. Les Vêpres Siciliennes isn’t great Verdi by any

means, but it’s a side to Verdi that we rarely see in his most popular

works, and it’s thrilling for that alone. We can be grateful to the

Nederlandse Opera for bring the full opera in its full original form

(with only one slight tweak of the placement of the Overture), but also

to have a director like Christof Loy, who clearly cares enough to put

the additional effort into making the opera relevant and meaningful.

The quality of the Blu-ray

release from Opus Arte is good, if not exceptional. The large mostly

dark stage and stark lighting makes it difficult to get an entirely

satisfactory exposure level, but the image is relatively clear, the

opera well-filmed and there are no noticeable defects. There’s not much

to choose between the LPCM Stereo and the DTS HD-Master Audio 5.1 audio

mixes. The surround track is firmly to the front and centre, with little

but ambience in the rear speakers. The 2-channel mix, by the same token

eliminates some of the reverb. Otherwise, both tracks are more than

adequate for a live recording, achieving a good balance between singing

and the orchestra. The half-hour Introduction to the opera is an

entertaining and informative look mainly behind the scenes at the

rehearsals and presentation of the opera.

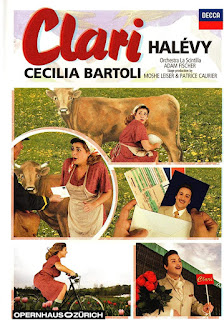

Jacques Fromental Halévy - Clari

Opernhaus Zürich, 2008

Adam

Fischer, Moshe Leiser & Patrice Caurier, Cecilia Bartoli, John

Osborn, Eva Liebau, Oliver Widmar, Giuseppe Scorsin, Carlos Chausson,

Stefania Kaluza

Decca - DVD

It’s very rare to see any work

by Jacques Fromental Halévy performed nowadays, and he may indeed be an

unjustly neglected composer, but discovered by Cecilia Bartoli while

exploring the repertoire of the famous Rossinian mezzo-soprano Maria

Malibran, this early work, Clari from 1828, composed to allow

her to demonstrate her extraordinary range, is certainly one of his most

obscure and forgotten works by the composer. Respectfully played with

period instruments by the Zurich La Scintilla orchestra under the baton

of Adam Fischer, treated to a fresh production from Moshe Leiser and

Patrice Caurier to give some character to a dreary and uneventful plot,

and with Bartoli demonstrating her wonderful vocal range, Zurich Opera

certainly give the opera a fair shot, but whether Clari is an

opera that merits such treatment is debatable, and the overall feeling

is that it really wouldn’t have been such a great loss if it had

remained buried.

Composed for an Italian libretto, before Halévy’s more famous, or at least more celebrated, French opéra comique work, Clari is an opera semiseria,

which doesn’t mean that it’s only half-serious and plays its silly plot

out with tongue firmly in cheek (although the production half-heartedly

and perhaps out of necessity plays it that way). Rather, it’s a kind of

mixture of opera seria (long after it had gone out of fashion even in 1828) and bel canto, full of long arias pondering internalised emotions expressed with extravagant coloratura in the da capo

singing. This is fine if an opera has an involving plot and strong

characterisation that can bear the weight of all the deep expressions of

guilt and shame that are agonised over in Clari, but the story is not so much ludicrous as flat and pedestrian.

It involves a young peasant

girl, Clari, who leaves her family in the provinces and runs off with a

rich Duke in search of wealth, a better life and, most importantly love –

or at least at the bare minimum, marriage. The Duke however hasn’t

fulfilled his promises in this respect – to the great shame of her

parents – and when he starts referring to Clari as his cousin, the young

woman is further dismayed with the situation she is in. When the Duke’s

servants Germano, Bettina and Luca put on a play for Clari before

assembled guests at a birthday party in her honour, the story so

resembles her own situation that Clari – believing it to be real (!) –

faints out of shame. That’s about as far as any plot goes in Act I. Act

II has each of the characters agonise over the situation until Clari

eventually recovers from the shock and decides she has to run away,

returning to her home in the country to try to gain the forgiveness of

her parents in Act III.

As far as dramatic and

emotional content, that’s about as far as it goes. One doesn’t

necessarily expect a complex or credible plot in a bel canto

opera, but really, the libretto, by Pietro Giannone, is pretty banal and

sparseness of the plot and hollowness of the emotional charge scarcely

merits all the moaning and wailing about wanting to die of the shame and

guilt of it all that is expressed at length in the arias. None of it

feels sincere, although it not for want of trying on the part of the

performers or the stage direction team. Leiser and Caurier go for a

non-specific relatively modern time period, glitzy and colourful with

big props in the style of Richard Jones, adding humorous and

self-knowing little touches, but none of it is enough to breathe any

life into this corpse of an opera, and their efforts consequently feel

leaden and fall flat.

The Zurich audience don’t seem

to be sure what to make of it either, laughing politely at one or two

places, but are clearly bewildered about what to make of the character

of Clari herself or the amount of effort and technique Cecilia Bartoli

expends on the empty phrases of the libretto, all in the vain attempt to

make her character come to life. It’s only in Act III that they

belatedly decide to applaud the efforts of John Osborn’s Duke and give

an enthusiastic and deserved ovation for Bartoli – but one feels they

might have mistaken her gargantuan efforts as signaling the end of the

opera a little before its time. Eva Liebau as Bettina and Carlos

Chausson as Clari’s father also make notable contributions, but it’s

hard to take their roles seriously or indeed “semiseriously”.

Released on DVD only as a

2-disc set, the colourful qualities of the staging suffer a little from

the lack of a High Definition presentation. The image looks reasonably

well in the brighter sequences, but it’s a little murkier in the scenes

at the end of Act II and start of Act III. Perhaps being spoilt by DTS

HD-Master Audio mixes, the quality of the audio lacks precision of tone,

particularly on the lower frequencies, but it’s actually not bad on

either mix, although I think the LPCM Stereo wins out over the DTS 5.1

Surround. There are no extra features on the DVD set, but there is a

worthwhile booklet enclosed which includes an interview with Bartoli, an

introduction to the work, productions notes, a synopsis and even a

photo-novella of the opera.