Monday, 30 October 2017

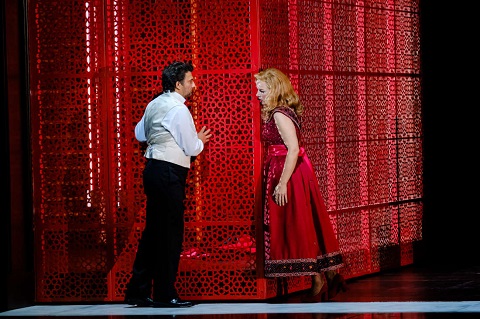

Wrainwright - Prima Donna (Armel, 2017)

Rufus Wrainwright - Prima Donna

Armel Opera Festiival, Budapest - 2017

Gergely Vajda, Róbert Alföldi, Je Ni Kim, Mária Farkasréti, Máté Sólyom-Nagy, Botond Ódor

ARTE Concert - 19 July 2017

There are certain risks associated with writing an opera about opera, unless you are Richard Strauss and have Hugo von Hofmannsthal as a librettist. Which, as that obviously implies, means that you have a lot to live up to. Somewhat in the thrall to Romanticism then and in complete contrast to most contemporary opera composition Rufus Wrainwright's first opera Prima Donna is, to say the least, a little florid if not actually musically and dramatically overwritten. On the other hand, as an opera that is essentially about the great opera tradition, you can excuse its excesses to some extent, particularly when it's done as well as this.

Dealing with a great opera singer living in seclusion and fear of her decline in a Paris apartment, Prima Donna is clearly inspired by the fate of Maria Callas. In a Paris apartment, Régine Saint-Laurent, a former great opera singer is looking back over her career. She hasn't sung in public since the acclaimed premiere of 'Aliénor d'Aquitaine' six years ago, singing a role one that was written for her, one she believes was the greatest role of her career and indeed one of the greatest parts in any opera. But the opera was in some way cursed, and the great diva's voice failed her on the night of the second performance. She hasn't sung it or any opera in the six years since, even though the press still show considerable interest in speculating at her making a comeback.

The success of Wrainwright's opera lies in it being more than just a loving tribute to an opera diva, and it even extends beyond the belief (and successful demonstration) of the power of opera to permit one to dream. There's also an essential human side to the story that it is essential to tell, and that's more than just the tragedy of the loss of greatness, the acceptance of the failing powers, the diminution of talent and genius, or the ending of a dream. In many ways it's also about acceptance that change is inevitable and that all things come to an end.

Prima Donna has a small cast, but none of them are supporting roles. In their own way each has singing challenges as great as those given to someone playing a grand diva, but they also support the wider implications of the work. Philippe, Madame Saint-Laurent's majordomo, is perhaps the one with the greatest delusions, and the one who has the hardest time accepting the fate of his mistress. He is someone who believes he has powers, managing (invisible?) servants around, arranging for a journalist to help give Régine the confidence to return to the stage.

For a while Philippe, Marie the maid, Régine and the journalist all fall into the thrall of this dream. The journalist, professing great love for the legend of her last great performance, encourages Régine to momentarily relive the experience, singing pieces from 'Aliénor d'Aquitaine', and Wainwright scores and sets the scene admirably. The rather Saint-Saëns-like opera within an opera does indeed seem to aspire to a greater place, to transport the participants and the listener to another world, only for the reality to come crashing back in.

The musical reference points are what you might expect; hints of Wagnerian Romanticism; lush Puccini-like orchestration, numbers and sentiments; even some Janáček rhythms and structuring, with Emilia Marty of the Makropulos Case an evident reference point, but there's also an element of Jenůfa and The Cunning Little Vixen in those deeper themes of dreams giving way to the acceptance of the harsh but undeniable realities of life. Conductor Gergely Vajda handles this without any suggestion of pastiche or irony as Wainwright's music has its own character and is closely related to the subject itself.

Whether the work touches on a deeper human element or remains lost in its own little world of opera could depend very much on how it is presented in any given production. The staging created by Róbert Alföldi specifically for the Armel Opera Festival competition in Budapest is simple but effective. It relies on the fact that the opera has a single physical location and a small cast of singers, and makes the most of them to transport the work into those other essential areas. The main transformation takes place in the appearance of Régine, between when she is over-dressed as the diva and shuffling around the apartment without her wig in a bathrobe. There are other little tricks of lighting and a 'spot-lit' platform that can transform the location and mood in a second, which this opera often does.

It shouldn't be underestimated however just how challenging the singing is for all four roles here. The female roles are really in the Richard Strauss register, dramatically and technically challenging for Mária Farkasréti's Madame Saint-Laurent, who also has to show an edge of vulnerability for the role of a great singer losing her voice to be credible. The high tessitura for Marie the maid calls for a light agile voice and Je Ni Kim (in competition) reaches those stratospheric heights impressively while retaining a sense of musicality. The journalist is also at the high end of the tenor voice, and Botond Ódor shows just how lyrical and beautiful that can be. Máté Sólyom-Nagy sings the baritone role of Philippe authoritatively and with sensitivity. The Armel production of Prima Donna is a very fine showcase for Wainwright's abilities as an adventurous and capable composer.

Links: Armel Opera Festival, ARTE Concert

Thursday, 26 October 2017

Verdi - Don Carlos (Paris, 2017)

Giuseppe Verdi - Don Carlos

L'Opéra National de Paris, 2017

Philippe Jordan, Krzysztof Warlikowski, Jonas Kaufmann, Elina Garanča, Sonya Yoncheva, Ludovic Tézier, Dmitry Belosselskiy, Ildar Abdrazakov, Eve-Maud Hubeaux, Julien Dran, Krzysztof Baczyk, Hyun-Jong Roh

Opéra Bastille - 22nd October 2017

For anyone used to the more familiar Italian version, the rarely performed original French version of Verdi's Don Carlo/Don Carlos presented at the Paris Opera could sound rather subdued and lacking the heightened emotional state one expects for this work. Even though we are very much in the domain of the 5-Act grand opera there does however seem to be some merit in adopting a more gentle approach for the French language version. If Philippe Jordan exercises restraint in the Paris Orchestra and Krzysztof Warlikowski reigns in his usual directorial excesses, the premier league cast assembled here are at least capable of finding the necessary dynamic in the contrasts of character.

One need only read and listen to the more gentle flow of the French language libretto, composed in verse and in rhyming couplets, to see that it requires a different approach from the language of the the Italian text, which in Verdi can tend towards bombastic. Don Carlos and indeed Don Carlo should never be bombastic, since the nature of Schiller's treatment of the historical drama is more reflective and interiorised conflict, exuding an air of dark melancholy and sometimes even a bleak outlook on the nature of man.

That tone is established right from the outset in Warlikowsi's production, with Jonas Kaufmann's Carlos wandering onto a bare wood-panelled set in a state of suicidal despair, his bleeding wrists wrapped in bandages. That's not how we usually see the Fontainebleau scene in the 5-Act version of the opera - with Elisabeth already in her wedding dress alongside a white horse - but it appears that the director wants to visualise this vital but usually truncated Act as a fevered dream flashback, combining Carlos's Act II gloomy meditations on death at the tomb of Charles V in the cloister of the Convent of Saint-Just, with his disappointment over the outcome of his expected engagement to Elisabeth.

Aside from a rather more abstract-modern presentation of the scenes in the locations and costumes, Krzysztof Warlikowski and dramaturgist Christian Longchamp don't apply any other real conceptual twists on the subject. The sets are elegant and economic with the space of the Bastille stage, but yet they can be suitably grand when the occasion demands. The auto-da-fé scene for example manages to get a sense of the horror with an overlay of a silent-era film projection of a giant devouring a man. It's simple and impressive, without having to fall back on clichéd imagery or mannerisms (or indeed Warlikowski-isms) that nearly always fails to effectively represent this scene in the opera.

On the other hand, Warlikowski's usual mannerisms are missed here, or at least his ability to bring focus and draw attention to the complex levels of a work like Don Carlos is lacking. The intention is to lay bare the Oedipal and Hamlet-like Shakespearean side of Verdi's reading of Schiller, with all of its character contradictions and relationship complications, but it never really gets to the heart of the work, much less find any way of overcoming the opera's dramatic and structural weaknesses. The inclusion of the indispensable Act I Fontainebleau scene and the exclusion of the dispensable ballet scene go some way towards making the work flow better, and greater emphasis is well placed on the dominant father aspect of the work by focussing on Charles V, but the roles of Rodrigo and Eboli add other dimensions that aren't as fully explored. At least, not in the dramatic context.

In terms of singing it's another matter, and ironically the performances of Posa and Eboli by Ludovic Tézier and Elina Garanča are so good that they balance out (and almost overshadow) the focus of the production on the patriarchal power play by restoring some measure of importance on the work's consideration of love, friendship, jealousy and rejection that their characters provide. The weight of those aspects of the work are almost all expected to be covered here by Philippe II, and Ildar Abdrazakov does give an outstanding performance, but it neglects the riches that can be found in the different nuances provided by Eboli and Rodrigue.

Perhaps however the strength of those performances, in conjunction with Philippe Jordan's subtle handling of musical dynamic, are enough to convey everything that is required. It certainly felt like it. Ludovic Tézier's smooth baritone is full of heartfelt expression that suggests a warm and loyal friendship with Carlos, but with an edge that revealed some of his personal conflict in his duty to the King and his belief in the Flemish cause. His performance of Rodrigue's death scene was loudly applauded and it seemed to me that he deservedly got the longest and most enthusiastic acclaim at the curtain call too. Elina Garanča wasn't far behind him though. With great stage presence and tremendous delivery, her Eboli carried force of conviction and yet tenderness and regret. Her 'O don fatale', summing up her predicament, was pretty much devastating.

That kind of conviction and delivery carried through to the back of the hall to those of us in the cheaper seats, and that was the case also for Ildar Abdrazakov. Without underestimating the greater challenges that the roles of Carlos and Elisabeth carry however, the same can't be said with as much certainty for Jonas Kaufmann and Sonya Yoncheva. Kaufmann's usual strength and force is all there and his delivery impassioned, but he doesn't have the volume to fill a hall the size of the Bastille. The detail of his performance worked much better I found when I subsequently watched scenes from the streamed performance of this Don Carlos on ARTE. Sonya Yoncheva wasn't perfect in her delivery either and felt somewhat detached, but I personally have never heard anyone sing the challenging role of Elisabeth perfectly, and Yoncheva at least is one of the best I can recall.

Such challenges and imperfections are perhaps in the nature of Don Carlos, and may indeed be the very reason for it remaining always such a fascinating work, since Verdi's venture into French grand opera neither fits to the tradition of Meyerbeer, Halévy and Auber, nor is it merely an Italian opera in French guise. Warlikowski and Jordan succeed then in some areas and fail in others, which is perhaps an inevitability with this work. You can't fault a cast as impressive as this either - you really can't do justice to Don Carlos without a cast as stellar as this - and Jordan's French touch does reveal other interesting aspects of the work. With its complicated blend of history, personal drama and the fantastical and that problematic ending that I've only seen Robert Carsen approach in any way half-convincingly (although it required much manipulation in his 2016 Strasbourg production), the perfect or definitive version of Don Carlos still remains elusive.

Links: L'Opéra de Paris, ARTE Concert

Wednesday, 25 October 2017

Manoury - Kein Licht (Paris, 2017)

Philippe Manoury - Kein Licht

L'Opéra Comique, Paris - 2017

Julien Leroy, Nicolas Stemann, Sarah Maria Sun, Olivia Vermeulen, Christina Daletska, Lionel Peintre, Niels Bormann, Caroline Peters

Salle Favart, Paris - 21st October 2017

Kein Licht is not strictly speaking an opera. It's so avant-garde that the composer Philippe Manoury had to come up with a new term to describe it; a Thinkspiel. Or, to give it its full title, it's "Kein Licht (2011/2012/2017): A Thinkspiel by Philippe Manoury and Nicolas Stemann, for actors, singers, musicians and real-time electronic music, adapted from a text by Elfriede Jelinek". It doesn't sound all that different then from most contemporary operas and Kein Licht isn't as ground-breaking as it thinks it is, but there are certainly some new and quite surprising innovations here.

Kein Licht is however at least a very considered work, one that not only strives to deeply examine its subject, but also tries to consider what role of a contemporary opera is and how it can best reach an audience. A contemporary opera should use all the resources at its command; theatrical effects, projections, 3-D graphics, electronic music, amplification if necessary, actors as well as singers, and it should use all these means to deliver a message that is relevant, entertaining and accessible even to an audience who wouldn't go to a traditional opera. Kein Licht does well on most of those points, but I'm not so sure about the last one.

It certainly has the best of intentions. Instead of spending a year writing, composing, rehearsing a work that would at most get four performances in a Paris theatre, there was clearly a greater effort to extend the life and the outreach of Kein Licht. It was developed as a co-production with the Ruhrtriennale, the Opéra national du Rhin and the Festival Musica in Strasbourg where it played before making its opening at the newly restored Salle Favart of the Paris Opéra Comique. Crowd-funding also played a part in the work's creation, and the word has been spread through extensive promotion, radio interviews, scientific conferences, YouTube videos and a radio broadcast of the Festival Musica performance. This performance on the 21st October at the Opéra Comique was captured on video for a live web broadcast. There was clearly a great belief in the project and an effort to get it out there.

It's all the more important that the resources put into creating Kein Licht reach a wide audience, since the opera is indeed about making the best use of energy, or to be more precise, it's about how we unthinkingly consume the world's resources without any consideration of the consequences. The jumping off point for consideration of these themes is a series of writings by Nobel Prize winning writer Elfriede Jelinek following the 2011 meltdown of the Fukushima nuclear reactors in Japan. Director Nicolas Stemann, who has worked on lyrical and dramatic presentations of Jelinek's texts before, notably with Olga Neuwirth, worked with composer Philippe Manoury to bring these thoughts to the stage in what would appear to be the only way possible; in a 'Thinkspiel'.

The manner in which the subject is approached is plain enough, but the presentation is a little more complicated. A lot more complicated actually. Jelinek's thoughts on the subject are divided into the three parts of the time of their writing - 2011, 2012 and 2017. Part I - 2011 deals with thoughts around the disaster of Fukushima and the danger (and the actuality) of its warning not being heeded. Part 2 - 2012 then looks at a world in denial, even as the disaster unfolds, people taking selfies as the world falls apart around them, belatedly realising that they soon won't have power for the batteries of their iPhones. Part III - 2017 has the more difficult task of looking at where we are now in a world that appears to be rushing headlong into madness, with global warning being ignored and disputed, with nuclear warheads being launched, and Trump at loggerheads with North Korea.

That makes Kein Licht sound rather more coherent than it actually is. Jelinek's texts, imagery and associations are often obscure, even if what lies behind them is clear enough. There is obviously no dramatic narrative as such and no characters either in the Thinkspiel. Two actors A and B perform/declaim/act out the texts and the suggestion is that they can be seen as opposing aspects of the human conscience, or as elementary particles in nuclear physics, while four singers (mezzo-soprano, soprano, contralto and baritone) and a chorus also with undefined roles provide lyrical expression of the ideas on a set of leaking nuclear reactors that collapses into complete meltdown leaving a flooded world. In terms evoking an appropriate mood, it's certainly representative of a state of chaos in thinking and in behaviour.

As the title Kein Licht perhaps indicates, Manoury references Stockhausen, albeit adopting a contrary position ("Without Light") to Stockhausen's cycle of a utopian vision in Licht ("Light"). Musically too, Stockhausen is an undeniable influence as one of the great electronic music innovators and visionaries. Manoury relies on many of the same extended techniques, but does take things further. Thanks to modern technology and research developed by IRCAM, Manoury is able to be freer with live electronics, auto-generating music that is responsive to live performance, synthesising live singing with the sound world to create new musical sounds. Some of it - most of it - is lyrical, dramatic, plaintive and creative. The howl of a live dog 'sings' at the start of Part I for example, and in Part II is joined by the other singers howling to create the most extraordinary live chorus unlike anything else in music.

Such innovations are to be found throughout Kein Licht, in the music performed by United instruments of Lucilin and conducted by Julien Leroy and in the theatrical presentation that creates 3-D graphics in real-time. While it is a fascinating work from that point of view and unquestionably responsive to the subject, the treatment and the situations, it does still feel a little over-worked to the cost of delivering the important message in the most effective manner possible. Manoury himself appears on stage and on live projection as part of the performance, explaining the musical ideas, what we are listening to and what we are seeing, which does unquestionably help understand what the creators are trying to get across. A synopsis given out at the theatre also proves essential to following what is going on, otherwise Kein Licht could prove to be just too clever and risk leaving its audience completely bewildered.

Kein Licht has to be seen on those terms, replete with its footnotes and commentaries. Which is not to say that it fails in its endeavour since it's not conventional theatre or conventional opera that tells you what it thinks or plays out a drama. It is indeed a Thinkspiel and that means that it is about bringing in involvement and being responsive to it, looking at itself and being reflective. It's even self-critically aware that it is part of a hugely wasteful capitalist system and as such a drain on precious resources that the planet will eventually have to pay for, but that's all part of the complicated A/B dialectic that the viewer themselves has to come to terms with. Entertaining, innovative and thought-provoking but chaotic, contradictory and often confusing, the response to Kein Licht is likely to be similarly divided.

Links: L'Opéra Comique, ARTE Concert

Friday, 20 October 2017

Prokofiev - The Gambler (Vienna, 2017)

Sergei Prokofiev - The Gambler

Wiener Staatsoper, Vienna - 2017

Simone Young, Karoline Gruber, Dmitry Ulyanov, Elena Guseva, Linda Watson, Misha Didyk, Thomas Ebenstein, Elena Maximova, Morten Frank Larsen, Pavel Kolgatin, Marcus Pelz, Clemens Unterreiner, Alexandru Moisiuc

Staastoper Live - 7th October 2017

Sergei Prokofiev's desire to write an opera based on Dostoevsky's The Gambler is an interesting one and comes at a significant point in Russian history. The Gambler is a short novella, but it deals with some fundamental Russian characteristics and behavioural traits that Prokofiev converts to the opera form in a stark and original manner. It's as if the composer were exploring the Russian character in a classic piece of literature and experimenting with it in a new form of musical expression. Completed in January 1917 however, Russia was about to embark on its own new direction with the 1917 February Revolution, leaving Prokofiev's opera unperformed and the composer himself soon afterwards going into exile.

The essential tone of The Gambler however is determined by its original author Fyodor Dostoevsky. Although it can be read as such, this was no academic study of the Russian propensity to throw their lives into the maw of fate, irrationally risking everything on the turn of a roulette wheel. As with much of Dostoevsky's work, The Gambler has the tortured quality of the author's own personal experience. That's vividly expressed in the writing and Prokofiev's brilliance was his ability to convert that obsessive quality into a driving dynamic music that pushes boundaries and yet remains essentially Russian in its character.

There's something of a revolutionary spirit in Alexei Ivanovich, or at least - since his concerns are very much self-obsessed - there's a certain disregard for the social order that he sees around him in the casino of a German spa town. 25 years old, university educated and employed as a tutor for Russian family, Alexei believes he's as good as any of the titled aristocracy and worthy of the love of Polina, the stepdaughter of the General. He's scornful of the bourgeois lifestyle, where they are always concerned about money and never happy. The General himself has debts to pay however, so Alexei knows that he needs to have money if he is to woo Polina away from a French Marquis who has given the family a loan.

Alexei's "Tatar nature" however has led him to see gambling as an alternative means of acquiring wealth and happiness and earn the respect of Polina. "Money is everything", he tells her, "You would see me differently. Not as a slave". But he has exhausted the savings of his salary and lost the huge sum of 6,000 guilders playing roulette at the casino. The General is worried at the instability and lack of rational behaviour that Alexei exhibits, and has to apologise on his behalf to try and prevent a duel with Baron Wurmerhelm when the tutor calculatedly goes out of his way to insult the Baroness.

The General however is soon rather more concerned about equally reckless behaviour that threatens to undermine his own financial prospects and his marriage to his fiancée Blanche. He has been depending on an inheritance from his grandmother, Babulenka, who he has told Blanche is at death's door, but the old lady has turned up in town and is gambling and losing every last crown of his future inheritance at the casino.

The Gambler, like Pushkin's Queen of Spades, like Tolstoy's Pierre in War and Peace (and Tolstoy's own early life of aristocratic dissolution and gambling debts) deals very much with that self-destructive tendency in the Russian nature to throw oneself at the hands of fate where the stakes are winning all or losing everything. There's no half-measures. There's a self-contradiction in the position of Alexei who has ambitions towards acceptance and respectability in this society and also in the General who values honour and reputation. It seems that there is also a certain amount of concern about keeping up such appearances and measuring up to their international neighbours, with Germans, French ad English all present in this setting.

Karoline Gruber's direction of the Vienna State Opera's new production of The Gambler attempts to bring together all the colour and contradiction of the positions expressed in the work, along with all the madness that ensues when alcohol is added to the mix. The set depicts the German town as a fairground ride, a merry-go-round on a Russian roulette wheel, which is lot of metaphors to mix that don't necessarily go together, but then neither does the Russian psyche depicted by Dostoevsky and Prokofiev, which is complex and contradictory at war and at play. The costumes are cartoonish and caricatural, with Baron and Baroness Wurnerhelm looking like something out of Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, and the gamblers in the casino and Alexei transforming into half-reptilian monsters.

It all looks terrific, with plenty of gold glitter thrown as well, creating a fantastical, non-naturalistic look that probes the deeper nature of the work. The larger-than-life character can also be applied to Prokofiev's score and Simone Young conducts to bring all that wild dynamic out of the orchestra performance. Rather than see it a collection of scenes, Young brings a greater sense of the work as a grand canvas that has coherence, is constantly building and upping the ante, marching towards an inevitably dramatic conclusion.

The greater coherence of the work is also brought out in the excellent singing performances. Alexei was one of the first roles I saw Misha Didyk singing (in the Barenboim/Tcherniakov 2008 Berlin Staatsoper production), and it's still one of his best roles. He can be a little strained elsewhere, but is generally more contained in the Russian repertoire and doesn't let Alexei slip overboard into wild madness - or at least not too early anyway. There's terrific singing also from Linda Watson, full of character, poise and recklessness as Babulenka; Elena Guseva is an impressive Polina, the role well sung and played with an appropriate sense of coolness gradually dissolving as Polina recognises that she has no control of her own fate. Dmitry Ulyanov plays the exasperated General well, but Elena Maximova's Blanche could do with a little more character and fieriness.

Links: Wiener Staatsoper, Wiener Staatsoper Live

Monday, 16 October 2017

O'Dwyer - Eithne (Dublin, 2017)

Robert O'Dwyer - Eithne

Opera Theatre Company, Dublin - 2017

Fergus Sheil, Orla Boylan, Gavan Ring, Robin Tritschler, Brendan Collins, Eamonn Mulhall, Imelda Drumm, John Molloy, Robert McAllister, Rachel Croash, Eoghan Desmond, Fearghal Curtis, Conor Breen

National Concert Hall, Dublin - 14th October 2017

Economies of scale and a troubled political history have prevented the idea of a national opera from ever really being able to establish a foothold in Ireland. It's only recently that steps have been taken to form a national opera company to replace Opera Ireland, one of the arts victims of the economic crisis that struck Ireland almost a decade ago. Irish National Opera doesn't officially come into being until 2018, but in the meantime a few of the component groups that will form the new company have been working hard to keep opera alive in the country. There has been a resurgence in contemporary opera commissions in recent years and now, quite thrillingly, there's been the rediscovery of one of the most important works in the history of Irish opera, Robert O'Dwyer's Eithne.

Eithne has the distinction of being the first full-scale opera composed in the Irish language. It was composed in 1909 by Robert O'Dwyer, who was born in Bristol of Irish parents, and the opera was last performed at the Gaiety theatre in Dublin in 1910. As the fate of Ireland was caught up in the subsequent years with the War of Independence and the Irish Civil War, O'Dwyer's Irish language opera was lost and only rediscovered when the orchestral score came up for auction in 2012. It was an occasion of some national pride then to have the opera - unheard for over 100 years - reconstructed, revived and performed once again in 2017 by the Opera Theatre Company. While Eithne is no lost masterpiece, it is nonetheless an important and even an impressive work, and it certainly impressed the audience who came to see in a one-off concert performance at the National Concert Hall in Dublin.

An unheard work by an unheard of composer, it was difficult to imagine beforehand what to expect from Eithne and just how it was going to sound. The period of composition and the subject based on Celtic mythology however gave a few important clues and indeed the few on-line rehearsal clips posted in advance suggested a lush post-Wagnerian romanticism. In the event, there is little that is Wagnerian or even Straussian in Eithne's scale or ambition, and the music itself isn't particularly Celtic sounding, although there is a fairy-tale element to the harp music and a folk element in some of the solo violin playing. It's the rhythms and sounds of the Irish language however that provides a more recognisable character for the folk legend of Eithne, aligning it more closely to Dvořák and the fairy-tale romantic character of Rusalka.

There is a recognisable connection with Die Zauberflote and Siegfried and a romantic element too in the heroic endeavours of Ceart to become the High King of Ireland. Based on the legend of Éan an cheoil bhinn (The bird of sweet music), the Irish language libretto for Eithne was composed by the noted academic and playwright Tomás Ó Ceallaigh. In the first half of the opera, characterised by rousing choral music, Ceart is unanimously acclaimed by the people to be the successor to the High King, but his half-brothers Neart and Art conspire against him, claiming that he is responsible for the killing of the king's favourite hound. Nuala, who has brought Ceart up since the death of his mother, intervenes on his behalf and, evoking the songs of the birds when she speaks, she convinces the King of the truth and inspires him even to forgive Neart and Art.

The bird's song is heard again in the second half of the opera, and it leads the King away from the hunt. Surrounded by maidens, Eithne appears and tells of her fate, that she and her mother (Nuala) have been held captive in a spell by her father the King of Tír na nÓg (the legendary Land of Youth in Irish folklore). Ceart steps forward to challenge the Guardian Spirit of Tír na nÓg and beating him he acquires a magical ring, sword and cloak that will help him defeat the King. In order to break the spell however, Ceart has other challenges to face and, proving his worth as a warrior, as a worthy husband for Eithne and, as the death of his father is announced, as the High King of Ireland.

Evidently, there's enough magic and drama in Eithne for it to be a fine stage spectacle, and perhaps one day we might get the opportunity to see it that way, but this first and only presentation of Robert O'Dwyer's rediscovered work was presented to the Dublin audience in concert performance, where it was recorded for a future CD release. Even in concert performance, this was an impressive way to experience the opera, as it gave great opportunity not only to hear the individual singers but the work of the large chorus - so prominent through - and the terrific playing of the RTÉ National Symphony Orchestra conducted by Fergus Sheil, giving the lush melodic musical qualities of the work central stage.

Despite the title of the opera being granted to Eithne, who only makes an appearance late in the opera, it was Robin Tritschler's Ceart who was unquestionably the star performance of the night. The tenor has a beautifully light lyrical tone that is reminiscent of Klaus Florian Vogt in one or two places but with a little more 'body'. A virtuous, heroic tone is required for Ceart - if not quite of the Heldentenor variety - and Tritschler delivered that in abundance. The role of Eithne has challenges, but not perhaps of the Wagnerian level either, and I thought Orla Boylan (who I last saw singing the big role of Turandot) was a little too large a voice for the role in that respect, and there was some wavering as she tried to fit to the lyrical flow. Boylan however certainly carried the romantic heroism of the role with all the essential Irish qualities that are necessary there in her voice.

There were other impressive performances in Irish-singing cast. John Molloy's smooth baritone boomed imperiously as the rumbling Giant, the Guardian Spirit of Tír na nÓg. Nuala too has a substantial presence in the first act, and singing along to the flute birdsong accompaniment, Imelda Drumm was absolutely captivating. Gavan Ring, who was instrumental in bringing Eithne back to the stage, sang the role of the High King of Ireland wonderfully and in full possession of the elevated status of the role. The heightened Irish legend qualities were boosted considerably by the chorus of the Opera Theatre Company, bringing the audience to its feet at the opera's epic conclusion. It now seems that Irish national opera not only as a future, but it now has a glorious past history to look back on as well.

Links: Opera Theatre Company, Irish National Opera, RTE webcast

Tuesday, 10 October 2017

Mozart - La Clemenza di Tito (Glyndebourne, 2017)

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart - La Clemenza di Tito

Glyndebourne, 2017

Robin Ticciati, Claus Guth, Richard Croft, Alice Coote, Anna Stéphany, Michèle Losier, Clive Bayley, Joélle Harvey

Glyndebourne online - 3 August 2017

It seems to be the case that the success of a production of one of Mozart's opera seria works depends very much on how well it balances of all its different crucial elements. Mozart's music speaks for itself and in La Clemenza di Tito it's of a rare beauty and perfection; almost too beautiful for the nature of the turmoil and sentiments of the work, until you realise at the conclusion that this sense of order and reconciliation is precisely the point of the opera. The spoken dialogue in Mozart's work however is rarely given a consideration commensurate with the kind of attention to detail that is applied to the music.

In the past it's often been a case of cutting or rushing through the long stretches of recitative or spoken dialogue in Mozart operas to get back to the music. Christof Loy however demonstrated in an uncut Die Entführung aus dem Serail was how a work could be transformed when a director gave equal consideration to the mood and meaning of the spoken drama passages and had capable performers with good acting skills to deliver them. When both music and drama were given this kind of attention, there can be a remarkable synthesis between words and music, staging and performance, showing that Mozart's operas are more than just a collection of pretty tunes.

Robin Ticciati's conducting of the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment in the 2017 Glyndebourne production certainly demonstrates that there is more to the music than pretty tunes. He picks out the gorgeous detail of the composition and structure, highlighting the sonority of individual instruments and how they combine with the drama and sentiments of the work itself. Director Claus Guth characteristically looks beneath the surface and presents contrasting sides of the conflicted personalities involved in the opera's drama, but it's in how they give expression to the flaws in their nature - in the spoken sections as much as in the singing - that their humanity combines with Mozart's music to create a beautiful whole.

And when you see this opera done so well, its qualities as a complete opera are all the more evident. La Clemenza di Tito is more than a typical opera of expositional dialogue followed by static arias of love and anguish. The opera has some measure of dramatic interaction and action, but more importantly it has real human sentiments rather than generic interchangeable ones that drive these actions and give the arias a real sense of heartfelt meaning. In Mozart's hands, La Clemenza di Tito is more than a musical exercise and more than just a plot to hang some pretty arias off.

Here Tito's actions do not feel arbitrary or cruel. They reflect the real difficulties of ruling and trying to please everyone. Ruling it seems is not just a case of having your cake and eating it. We recognise Tito's wisdom in this matter early on when Servilia tells the emperor that her heart belongs to Annio but she is willing to submit to his will, and Tito renounces his intention to marry her. Likewise, when the cake offered is potentially poisonous, metaphorically speaking, as when Publio offers him a list of known political agitators who have been outspoken about the regime, Tito refuses to take any action against them. He certainly doesn't send in the riot police.

But a ruler is only as informed as his advisors allow him to be and only if his subjects are willing to speak without fear of retribution. Willingness to learn and forgive is all a part of La Clemenza di Tito and that's a characteristic that perhaps seems a little more idealistic when applied to the reality we know. And yet how attractive a proposition Mozart makes this seem. La Clemenza di Tito might appear unrealistic and naive in its treatment of the realities of politics and human nature, but the primary purpose of the opera is not to show a mirror to reality, but rather to show the potential of human nature and the rewards that we can strive to attain.

Claus Guth's production for Glyndebourne 2017 uses a split-level set design by Christian Schmidt to show to separation of the reality and the ideal and the conflict that lies between them. Guth recognises that the divisions are not as obvious as you might think, particularly in Mozart's view, where feelings of love and revenge can lie on the same side and are contrasted rather with duty and social/regal expectations that can blind one from seeing the truth. Guth also suggests a division between the spoken articulated word on one level and deeper sentiments and forces that drive one underneath. I'm not sure why Guth chooses to show the lower level as some kind of swamp, but there is a sense of seeking the truth in a more simple way of life, away from the duties of office.

What is also interesting about La Clemenza di Tito is that it's a work where, depending on the production, different figures can emerge as the key player, each expressing this split in nature versus behaviour. In some productions Sesto takes prominence as the character most prone to action and reaction. In others a forceful Vitellia can be the manipulator who provokes the troubles and then comes to regret her actions. It all very much depends on the strength of the direction of the performers, and while Anna Stéphany and Alice Coote are both excellent as Sesto and Vitellia in this production, it's Richard Croft's lyrical and sensitively performed Tito who emerges as a figure of real personality and character, showing genuine human concern for the role of a ruler and the anguish over the difficulties it involves.

Attention to the recitative is important, being able to get across the human feelings behind the words is vital, and Guth's direction forges a strong connection with Mozart's music as it is conducted by Robin Ticciati. Guth also has recourse to projections that hark back to simpler times, showing Tito and Sesto as children, but whether this is necessary or not, it provides another layer that fits in with all the other elements and gets to the human heart of Mozart's great final opera.

Links: Glyndebourne

Friday, 6 October 2017

Purcell - Miranda (Paris, 2017)

Henry Purcell - Miranda

L'Opéra Comique, Paris - 2017

Raphaël Pichon, Katie Mitchell, Kate Lindsey, Henry Waddington, Katherine Watson, Allan Clayton, Marc Mauillon, Aksel Rykkvin

ARTE Concert - 29 September 2017

You can't argue with the pedigree of the sources involved in the creation of Miranda. It's a 'new' opera based on characters in Shakespeare's The Tempest, set to music written some 300 years ago by Henry Purcell. And yet adapted by Cordelia Lynn Miranda is also a contemporary opera, set in the present day, with a very different outlook brought to the characters, the drama and the music by director Katie Mitchell and Raphaël Pichon.

The idea of creating a new opera out of existing material or adapting pieces to work in a new context isn't a new innovation in opera. Rossini frequently revised and cannibalised his own works in the 19th century - why waste a good tune? - but the practice is older than that. The pasticcio, an opera made of cobbled together 'hits' from other operas, was popular in the 18th century, and the practice was revived a few years ago for the Metropolitan Opera's The Enchanted Island (interestingly, also based around Shakespeare's The Tempest).

Katie Mitchell and Raphaël Pichon have good form in such matters, collaborating to create the sublime Trauernacht for Aix-en-Provence in 2014, an opera assembled out of cantatas by J.S. Bach. Whether it added up to a convincing dramatic piece was debatable, but the choice of music, the coherence and beauty of the sentiments expressed in bringing them together, certainly added up to a work that was greater than the sum of its parts. Even if you saw it as nothing more than a rare opportunity to bring Bach to the opera stage and hear some beautiful performances of his cantatas, there was merit in that alone.

The same unfortunately can't be said for how Shakespeare and Purcell are treated in the semi-opera Miranda. Shakespeare's The Tempest is pretty much jettisoned right from the start, or rather its themes and intent are casually dismissed by Katie Mitchell and librettist Cordelia Lynn in favour of a more feminist reading that sets out to "correct" the patriarchal attitudes and male power play expressed in the original. Miranda, now a young woman with a child, Anthony, has come to the realisation that she's been a victim of child abuse, and she's going to confront her aggressors; her father Prospero and her husband Ferdinand.

I'm not quite sure how the creators of this 'sequel' to the Tempest have come to this particular reading from Shakespeare's play or why they've chosen to ignore the multiplicity of other themes that can be found in the work, but the implication is that we've only heard one side of the story and it's been an exclusively male one. Miranda has had enough of being misrepresented and she's not going to take any more. It's time, she tells us, to tell the true story. She's accuses her father of forcing her into exile, permitting her to be raped by Caliban on the island, marrying her as a child bride and giving birth to a child when she was only 17. "You're an ego maniac", she challenges her father, "You need to shut up. I'm telling the story now".

Well, as you can see, in addition to being a rather dubious rewriting and imposition of a modern feminist perspective on The Tempest, Lynn's libretto lacks the finesse and poetry of Shakespeare's valedictory work for the stage. Miranda is also rather deficient in dramatic coherence, credibility and, well... taste basically. Miranda decides to stage her confrontation with her male aggressors in the most absurd way imaginable: as a terrorist hostage situation at a funeral where her family are mourning her death. Believed drowned, her body never recovered, Miranda has a surprise for the mourners, turning up at the church with a small terrorist unit, wearing a black mask and a wedding dress and waving a pistol in the faces of the shocked and terrified congregation.

It's nothing apparently to what Miranda has had to endure, and she sets the record straight with a pantomime act that fulfils the masque aspect of the semi-opera. The drama however doesn't really elaborate any further on the contention that "I was exiled. I was raped. I was a child bride", which is all Miranda seems to want to get off her chest. Having stage-managed this little melodrama for attention and revealed to an appalled Anna the true nature of her husband Prospero by whom she is bringing another child into this brave new world, it's all hunky-dory once again when Ferdinand begs forgiveness ('Then pity me, who am your slave / And grant me a reprieve' from O! Fair Cedaria); the presumption being - in the absence of any dramatic credibility or winning way with words - that the beauty of the sentiments expressed in Purcell's music is enough to make everything all right.

And in a way, it almost is. It's clear that there has to be some sort of dramatic compromise made in order to fit the chosen Purcell pieces into a coherent drama, and the suspicion is that the funeral is there to provide a suitable setting for a selection of Purcell's sacred music, the highlight here being the Evening Hymn 'Now that the sun hath veiled his light'. 'Dido's Lament' from Dido and Aeneas, sung here by Anna, does feel rather shoe-horned into the situation, but even in a situation as ludicrous as this the sincerity of the sentiments can't be denied in Miranda's forgiving/recriminating arias to Ferdinand, 'Oh! Lead me to some peaceful gloom' from Bonduca with the lines "What glory can a woman have / To conquer, yet be still a slave" ('woman' substituting 'lover' in the original) and to Prospero 'They tell us that your mighty powers above' from The Indian Queen.

The singers do their best to put some dramatic feeling into this, but there's not much for them to do as Miranda and Anna look sad and angry and take out their frustrations on Prospero and Ferdinand, who look embarrassed and ashamed. And that really sums up the very limited ambitions of Miranda, emasculating or reducing Shakespeare's achievements in The Tempest down to a one-way protest of anger and recrimination by women against men. Despite being shoehorned into such a situation, the beauty of Purcell's composition and sentiments still comes through in a way that makes Miranda more successful as a musical piece than a dramatic one.

Kate Lindsey obviously has the biggest say and platform here as Miranda and is excellent, firm and clear of voice if somewhat driven to over-expression by the drama. Katherine Watson also makes a good impression, but again the context of Dido's Lament doesn't perhaps permit its best expression. Allan Clayton and Henry Waddington have thankless roles (the brutes!) which they nonetheless sing well and are at least better fitted to their roles than Marc Mauillon's strained priest. Aksel Rykkvin's Anthony is worthy of a mention for a lovely performance of An Evening Hymn: 'Now that the sun hath veiled his light'. Despite my reservations about the libretto and direction, the qualities of Purcell's music and the performances here under the direction of Raphaël Pichon brought me back to watch this for a repeat viewing - much like Trauernacht - so there are certainly pleasures to be found here.

Links: L'Opéra Comique, ARTE Concert

Tuesday, 3 October 2017

Dennehy - The Second Violinist (Dublin, 2017)

Donnacha Dennehy - The Second Violinist

Wide Open Opera, Dublin - 2017

Ryan McAdams, Enda Walsh, Aaron Monaghan, Máire Flavin, Sharon Carty, Benedict Nelson, Alyssa Hefferman

O'Reilly Theatre, Dublin - 2 October 2017

The core elements from The Last Hotel, the first opera composed by Donnacha Dennehy with playwright and director Enda Walsh, are still in place in their second collaboration, The Second Violinist. The Crash Ensemble are still there to navigate through Dennehy's Irish trad-influenced rhythms; there's a small cast of three singers (two female and one male) and a male actor; even the subject plays on a similar theme of death and desperation. In most other respects however, The Second Violinist expands the range and ambition of both writer and composer, finely adjusting the balance of the various operatic components to create a fuller and more accomplished piece of music theatre.

In one respect there appears to be a simplification or at least a greater refinement and precision in this work's dramatic focus. The Second Violinist really all centres around one man; Martin is a musician, a second violinist (obviously) who appears to be on the verge of a breakdown. He's almost ready for a visit to the Last Hotel, by the looks of it. Like the Woman in that piece, Martin is bombarded by messages on his phone; he gets calls from a local drama group looking for incidental music for a production of 'An Ideal Husband'; constant promotional texts from a pizza company; and angry recriminations from Martin's colleagues who aren't too impressed with his lack of preparation at the last rehearsal.

There's a reason for Martin's distraction, and the reason for it eventually becomes clear - or sort of clearish in a complicated, twisty, mobius loop kind of way. Exasperated and visibly at the end of his tether, Martin finds that the apartment where he lives alone has been taken over by phantoms who act out what at first appears to be a fairly ordinary domestic scene. Married couple Matthew and Amy are having an informal evening with Amy's friend Hannah, having a few glasses of wine and a pizza, but as the evening continues, things go a little awry, causing Matthew to consider how well he really knows the woman he has been married to for four (or is it five?) years.

Martin meanwhile tries to pull his life together, trying his best to ignore this phantom scene that is playing out simultaneously in his apartment, but not managing terribly successfully. The fact that he hasn't screamed or killed anyone yet (as far as we know), means however that he must be just about holding it together. What is keeping him from falling apart is an unexpected phone chat exchange with Scarlett, a viola playing musician who also shares his love for the Italian Renaissance composer, Carlo Gesualdo. The outcome of the fatal social evening however is closing in on Martin at the same time as he is starting to see light at the end of the tunnel.

Without getting too clever and self-referential - since the work's overlapping time-split narrative structure is complicated enough - The Second Violinist looks at life as an opera. Not in the familiar sense of musically-heightened dramatic melodrama, but in the sense of someone - a musician - who is looking for something that will bring a sense of structure, purpose and meaning to his life and put it into some kind of context. Carlo Gesualdo's life and music are an inspiration in this respect (as it has been for other modern composers, notably Salvatore Sciarrino's Luci mie traditrici and George Benjamin's Written on Skin); a tumultuous life with bloodshed and violence that nonetheless gave birth to music of indescribable beauty and poetry.

The Second Violinist consequently places greater demands on the role that the Crash Ensemble have to play under the direction of Ryan McAdams. There are still hints of Irish traditional music underpinning the score, but less of a single rhythmic pulse and a greater variety of tone in a work that has a more complex fractured dynamic with overlapping, contrasting sentiments to convey. It demands a different kind of virtuosity that doesn't rely on individual musicianship as much as a close collaboration of a custom ensemble working together to create that complex shifting sound world.

That's particularly important here because The Second Violinist is much more reliant on instrumental musical expression working with the dramatic narrative than the virtuosity of vocal expression that was rather more conventionally used in The Last Hotel. Sharon Carty, Benedict Nelson and Máire Flavin all handle their individual lyrical pieces well (less abstract than the pieces in The Last Hotel) and a chorus extend the chamber arrangements of the work considerably, but since we are viewing everything through the perspective of Martin, it would seem appropriate that it's Martin's view of life as an opera that is expressed mainly through the music, as well as in the silent intense performance of perpetual motion that actor Aaron Monaghan brings to the main role.

The superb set designs by Jamie Vartan and Enda Walsh's direction are just as vital to the expression and kinetic momentum that is established between the musical performance and the drama. As well as having two levels (woods/apartment) to represent different layers of Martin's psyche, the opera makes good widescreen CinemaScope use of the stage, where multiple events happen at the once or in quick succession but the focus of attention is always clear. The use of projections are also effective, with text messages and phone apps representing another important layer of everyday 'reality' that we can all recognise, not just Martin. Death, when it comes, does not bring the kind of dramatic resolution that we are accustomed to find in an opera; life and how we cope with it, as The Second Violinist shows in a fast and furious 75 minutes, is much more complicated than that.

Links: The Second Violinist, Wide Open Opera, Dublin Theatre Festival

Wide Open Opera, Dublin - 2017

Ryan McAdams, Enda Walsh, Aaron Monaghan, Máire Flavin, Sharon Carty, Benedict Nelson, Alyssa Hefferman

O'Reilly Theatre, Dublin - 2 October 2017

The core elements from The Last Hotel, the first opera composed by Donnacha Dennehy with playwright and director Enda Walsh, are still in place in their second collaboration, The Second Violinist. The Crash Ensemble are still there to navigate through Dennehy's Irish trad-influenced rhythms; there's a small cast of three singers (two female and one male) and a male actor; even the subject plays on a similar theme of death and desperation. In most other respects however, The Second Violinist expands the range and ambition of both writer and composer, finely adjusting the balance of the various operatic components to create a fuller and more accomplished piece of music theatre.

In one respect there appears to be a simplification or at least a greater refinement and precision in this work's dramatic focus. The Second Violinist really all centres around one man; Martin is a musician, a second violinist (obviously) who appears to be on the verge of a breakdown. He's almost ready for a visit to the Last Hotel, by the looks of it. Like the Woman in that piece, Martin is bombarded by messages on his phone; he gets calls from a local drama group looking for incidental music for a production of 'An Ideal Husband'; constant promotional texts from a pizza company; and angry recriminations from Martin's colleagues who aren't too impressed with his lack of preparation at the last rehearsal.

There's a reason for Martin's distraction, and the reason for it eventually becomes clear - or sort of clearish in a complicated, twisty, mobius loop kind of way. Exasperated and visibly at the end of his tether, Martin finds that the apartment where he lives alone has been taken over by phantoms who act out what at first appears to be a fairly ordinary domestic scene. Married couple Matthew and Amy are having an informal evening with Amy's friend Hannah, having a few glasses of wine and a pizza, but as the evening continues, things go a little awry, causing Matthew to consider how well he really knows the woman he has been married to for four (or is it five?) years.

Martin meanwhile tries to pull his life together, trying his best to ignore this phantom scene that is playing out simultaneously in his apartment, but not managing terribly successfully. The fact that he hasn't screamed or killed anyone yet (as far as we know), means however that he must be just about holding it together. What is keeping him from falling apart is an unexpected phone chat exchange with Scarlett, a viola playing musician who also shares his love for the Italian Renaissance composer, Carlo Gesualdo. The outcome of the fatal social evening however is closing in on Martin at the same time as he is starting to see light at the end of the tunnel.

Without getting too clever and self-referential - since the work's overlapping time-split narrative structure is complicated enough - The Second Violinist looks at life as an opera. Not in the familiar sense of musically-heightened dramatic melodrama, but in the sense of someone - a musician - who is looking for something that will bring a sense of structure, purpose and meaning to his life and put it into some kind of context. Carlo Gesualdo's life and music are an inspiration in this respect (as it has been for other modern composers, notably Salvatore Sciarrino's Luci mie traditrici and George Benjamin's Written on Skin); a tumultuous life with bloodshed and violence that nonetheless gave birth to music of indescribable beauty and poetry.

The Second Violinist consequently places greater demands on the role that the Crash Ensemble have to play under the direction of Ryan McAdams. There are still hints of Irish traditional music underpinning the score, but less of a single rhythmic pulse and a greater variety of tone in a work that has a more complex fractured dynamic with overlapping, contrasting sentiments to convey. It demands a different kind of virtuosity that doesn't rely on individual musicianship as much as a close collaboration of a custom ensemble working together to create that complex shifting sound world.

That's particularly important here because The Second Violinist is much more reliant on instrumental musical expression working with the dramatic narrative than the virtuosity of vocal expression that was rather more conventionally used in The Last Hotel. Sharon Carty, Benedict Nelson and Máire Flavin all handle their individual lyrical pieces well (less abstract than the pieces in The Last Hotel) and a chorus extend the chamber arrangements of the work considerably, but since we are viewing everything through the perspective of Martin, it would seem appropriate that it's Martin's view of life as an opera that is expressed mainly through the music, as well as in the silent intense performance of perpetual motion that actor Aaron Monaghan brings to the main role.

The superb set designs by Jamie Vartan and Enda Walsh's direction are just as vital to the expression and kinetic momentum that is established between the musical performance and the drama. As well as having two levels (woods/apartment) to represent different layers of Martin's psyche, the opera makes good widescreen CinemaScope use of the stage, where multiple events happen at the once or in quick succession but the focus of attention is always clear. The use of projections are also effective, with text messages and phone apps representing another important layer of everyday 'reality' that we can all recognise, not just Martin. Death, when it comes, does not bring the kind of dramatic resolution that we are accustomed to find in an opera; life and how we cope with it, as The Second Violinist shows in a fast and furious 75 minutes, is much more complicated than that.

Links: The Second Violinist, Wide Open Opera, Dublin Theatre Festival

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)