Christoph Willibald Gluck - Iphigénie en Tauride

Opéra National de Paris, 2021

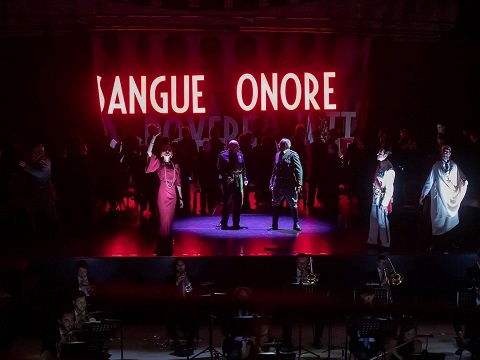

Thomas Hengelbrock, Krzysztof Warlikowski, Tara Erraught, Jarrett Ott, Julien Behr, Jean-François Lapointe, Marianne Croux, Jeanne Ireland, Christophe Gay, Agata Buzek

Palais Garnier, Paris - 26 September 2021

The essence of what is continually great and everlasting in the later works of Christoph Willibald Gluck is that despite the formality of the 18th century musical conventions and the poetic licence of contemporary adaptation, he manages to make the stories and predicaments of the great mythological figures of Greek drama feel completely human. Despite appearing to have a very limited idea for presenting the drama, Polish director Krzysztof Warlikowski's production of Gluck's Iphigénie en Tauride nonetheless similarly strives to find the underlying humanity in his production for the Paris Opera, and perhaps even delve deeper into the mindsets and troubled history of the Atreides family. The success of the production is mainly down to Gluck of course, but Warlikowski knows when to defer to genius.

Essentially, the Orestia deals with the downfall of a great family, a royal family, and assuming that they aren't really lizard people - something I'm prepared to keep an open mind about - even royal families are human too. Hmm. Anyway. Warlikowski has been here before - or rather later - with his Princess Diana influenced production of Alceste, and this production of Iphigénie en Tauride which was first produced in Paris in 2006, opens somewhat obscurely with a title 'Dedicated to Queen Marie Antoinette'. Other than it being about a royal family and it being produced for Paris, I'm not sure what the intention of that is, but it doesn't prove to have any real bearing on the rest of the production.

Warlikowski's setting for Iphigénie en Tauride is, well, it looks very much like most Warlikowski sets designed by Malgorzata Szczesniak, with glass panels, mirrored rooms, a wall of showers on one side and a wall of sinks on the other. Here Tauride is an old people's home where Iphigenia as an old woman in a gold lamé dress looks back at the defining incident in her experience of a troubled family life. Or not so much looks back on it of course as much as relives it, her mind failing, flitting between her current infirmity and mental state in old age and the incident on Tauride that may have helped reduce her to her condition.

This Tauride or old people's home is of course less a physical place than a state of mind, and it's the impact that her experience has on her mind that Warlikowski wants to explore. Within that however, the actual drama plays out much as you would expect, with Orestes and Pylades brought by the priestesses as strangers to be sacrificed at the paranoid King Thoades, who while trying his best not to fall victim to the fate an oracle has decreed for him, inevitably ends up bringing it about.

Warlikowski illustrates a few scenes behind the reflective shield of her mind, showing the now and the past, but it's fragmented and nightmarish in its visualisation and not a narrative illustration. Doubles are used, as they often are in productions of this work which seems open to such divisions and analysis, (Lukas Hemleb, Geneva 2015), (Claus Guth, Zurich, 2001) More than just use an actor to double Iphigénie past and present, internal and external, the director also doubles or contrasts the past as a mirror of the present. What plays out simultaneously is a kind of shadow nightmare scenario of her experience in Aulide, where it's now Iphigenia the priestess who is to carry out the human sacrifice, with Thoas becoming her surrogate father.

The psychoanalytical approach is quite appropriate, the dysfunctional family issues compounded with Iphigenia's encounter with the stranger who is her brother Orestes, and in Orestes seeing in Iphigenia the image of the mother he has just murdered. It's inevitable then that the familiar influence of the films of David Lynch also plays a part in this Warlikowski production, with scenes and imagery reminiscent of Wild at Heart (another horrific family saga of murder and brutality) and Mulholland Drive (a glamorous life on the surface with hidden horrors surfacing in the moment of death). Mix in a bit of royal scandal and there's plenty to make this visually impressive and troubling while still largely leaving the drama to tell its own tale.

Here, as is often the case, the best a director can do is find a suitable setting for mood and let Gluck's music and the drama speak for itself. Warlikowski does a little more than this, finding a way to bring the audience into the human drama that is playing out in the mind of Iphigenia. There are a few other touches, having the chorus and other players in the Tauride drama placed in the boxes, isolated and pushed off to the sidelines away from the wholly personal interiorised nature of Iphigenia's relationship with the drama. Diana's appearance at the end of Act 4 is appropriately sung from the back of the Palais Garnier up in the gods, all contributing to present as immersive a presence as possible of the drama replaying out in her mind.

Evidently it's Gluck's beautiful music, his attunement to the drama and the understated emotional states that drive the drama forward and it was successfully led from the orchestra under Thomas Hengelbrock. Vocally it was impressive also in the three leading roles. As Iphigenia Tara Erraught was superb, deservedly stepping into major opera house roles like this after a successful career as a repertory singer in Munich. Her musical range is consequently wide and varied, but she can do a leading Mozart role well (The Marriage of Figaro) and is certainly impressive in her French delivery of Gluck. Jarrett Ott was an excellent Orestes and Julien Behr offered strong lyrical support as Pylades.