Giuseppe Verdi - Aroldo

Teatro Galli di Rimini, 2021

Manilo Benzi, Emilio Sala, Edoardo Sanchi, Antonio Corianò, Lidia Fridman, Michele Govi, Adriano Gramigni, Cristiano Olivieri, Lorenzo Sivelli

Opera Streaming - 27th August 2021

A lot of time has passed since Verdi wrote Aroldo, and a lot of time has passed with Aroldo hardly being performed. A lot of time has passed also since its premiere in 1857 for the inauguration of the Teatro Nuovo in Rimini, so it's fitting that the opera should be performed there again for its reopening. The intervening years since Aroldo was first performed there have also seen a great deal of change and turmoil, including the destruction of the theatre during the war in 1943. Rebuilt after 75 years and now named the Teatro Galli, director Emilio Sala in some ways sees the fate of both theatre and opera intertwined or at least wants to use this production to bring together the shared history of the theatre and the legacy of this rare and by no means minor Verdi opera.

Aroldo may not be an entirely original work by Verdi, being a rework and rewrite of Stiffelio, but the history of the two works nonetheless span a pivotal period in the career of the composer. Stiffelio was written in 1850, just as Verdi was about to embark on his famous trilogy of Rigoletto, Il Trovatore and La Traviata, the work presaging themes and musical developments in these works, not least the protective father/daughter relationship of Rigoletto and with elements even of Germont's appeals to a fallen woman in La Traviata. Aroldo was then developed for Rimini in 1857 after these three masterpieces, with significant changes and a whole extra fourth act.

It's surprising then that Aroldo is not more widely recognised and is even less performed than Stiffelio. Even that work was only rediscovered relatively recently and successfully revived, a 1993 TV broadcast of a Royal Opera House production starring Jose Carreras and Catherine Malfitano a memorable discovery for me personally, remaining a personal favourite Verdi, but despite occasional revivals - usually for complete Verdi festivals - neither version has received due recognition as a strong work in their own right.

Part of the reason at least for Stiffelio's initial failure to gain a foothold in the repertoire is that it's quite different in several respects from the other early to mid-period Verdi works. It opens with wonderful solo trumpet led Sinfonia overture and it's overwrought drama is more of a domestic variety than that of any noble high society or great warrior leader. As a theme, guilt has more of a presence than the typical Verdi subject of revenge, although there's plenty of that too, albeit of a kind that fizzles out rather than end in bloodshed and tragedy. Unfortunately, the drama being based on a German Protestant minister, was also too different for Italian audiences and the censor not best pleased with a religious minister's wife being involved in adultery.

Verdi consequently reworked the opera in 1857, resetting it to England, the librettist Francesco Maria Piave extending and revising the opera with a fourth act, but Aroldo still retains much of the marvellous music and melodic invention of the original. Like most of Verdi's efforts to revise other works with concessions for ballet scenes in the French versions, chorus additions and cabaletta cuts made for the benefit of changing musical fashions, it's not a total success. As far as Aroldo is concerned, the reworking loses much that was fascinatingly different and already perfect in the original, but that doesn't make it the opportunity to compare a rare stage performance of Aroldo any less intriguing or exciting.

In the opening scene of Stiffelio, it is reported to the minister that a man has been seen jumping from the window of his wife Lina, leaving behind evidence that could identify him. The revelation, and the decision of Stiffelio to destroy the evidence without looking at it raises tensions from the outset, while here it's a little more subdued. Drawing from Edward Bulwer-Lytton's Harold: the Last of the Saxon Kings, Aroldo (Harold) returns from the Crusades and notices his wife Mina is not wearing her wedding ring, looking jumpy and guilty. Verdi raises the drama however more gradually and by the time of the slipping of a letter to her lover into a book, the drama has become more highly charged. 'Fatal, fatal mistero quel libro svelerà', buoyed by a chorus of scandalised onlookers is just as overwrought here as the original in Stiffelio. The extension however of the Act I conclusion 'Nol volete' after Mina's father's refusal to hand over the letter rather dissipates the tension that has been raised.

There is a similar picture throughout Aroldo. While the middle part of the work plays out much the same as in Stiffelio, with a duel and other situations for potential bloodshed averted, there is perhaps more of a similar sense of events heating up without ever quite boiling over. The intervening years between the two works that saw the creation of the mature Verdi's great masterpieces does indeed lead to evidence of a greater sophistication in the musical reworking, but Aroldo can also be seen consequently as being a little more conventional in the dramatic action than Stiffelio, with the rough edges that make the earlier work so interesting rather smoothed out even further in Piave's Act IV extension.

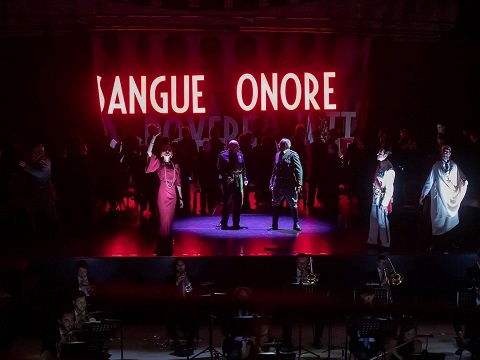

Under the direction of Emilio Sala and Edoardo Sanchi the 2021 production in Rimini does its best to reintroduce an edge by bringing the work together with the history of the theatre where it was first performed. It relocates the medieval English setting to the Italian war and colonisation of East Africa, changing references in the libretto from Palestina to Abyssinia and Eritrea. Instead of a storm in the new Act 4, projections and highlighted words align this with the bombardment of Rimini that destroys the town and the Teatro Nuovo on the night of 28th December 1943. The reconstruction of the theatre mirrors the rebirth of love between Aroldo and Mina, and the triumph of the divine. To further break down walls between the drama and real-life, the performers take this occasion to remove their costumes and wear their everyday clothes.

Reopened in 2018 after reconstruction, I imagine that the removal of the stalls seating to accommodate the orchestra was done more for the sake of social distancing. The opera is performed on the stage, the audience in the upper seating balconies. Aroldo is a typically demanding Verdi opera in the leading soprano and tenor roles. Lidia Fridman is quite impressive in the role of Mina, more than technically capable, she passionately throws herself into the role. Antonio Corianò struggles a little in the higher end of the dramatic tenor range, but is a good Aroldo. The performances are full of grand operatic gestures, but it's the nature of this opera and Verdi in general, and the Rimini production certainly matches the requirements at getting the quality of this work across very well indeed.

Links: OperaStreaming, Teatro Galli di Rimini