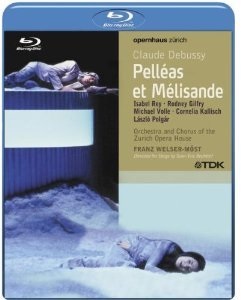

Opernhaus Zürich, 2004

Franz Welser-Möst, Sven-Eric Bechtolf, Rodney Gilfry, Isabel Rey, Michael Volle, Lázló Polgár, Cornelia Kallisch, Eva Liebau, Guido Götzen

TDK

Debussy’s only full-length opera, composed in 1902, could be considered somewhat difficult, and indeed part of the reason for its difficulty could lie in the composer consciously striving not to imitate Wagner. If the Wagner influence is still evident in Pelléas et Mélisande however, Debussy takes the idea of music-drama a little bit further, making it difficult to find conventional melodies, leitmotifs or even a clearly definable plot, the almost mythological storyline flowing rather to its own pace, rhythm and purpose. In reality, it’s not a difficult opera at all, unless you bring such expectations to it, but rather, left to work to its own unique operatic language, allowing yourself to go with the flow, it’s actually easy to become caught up in the strange world that Debussy creates.

The strange nature of the opera and the musical arrangement that it consequently adopts undoubtedly have more to do with the nature of the source work for the opera, a symbolist play by Maurice Maeterlinck that relates less to the conventions of narrative cause-and-effect drama, but more to the internal states of the characters being made manifest in the world around them through objects, environments, landscapes. Their behaviours are therefore less easily defined, unconstrained as they are by conventional means of expression and communication. Musically, this is also how Debussy’s score operates. Trying to associate the music with the singers through the traditional form of expression then can be problematic and not lead to expected rational conclusions. Much better to let those elements just seep in, create their own resonances that are less literal and more impressionistic and suggestive.

As such Pelléas et Mélisande is not an opera that needs to be tied to any specific period – unless a director wants to make a specific statement – and to tie it to a particular time or place is likely to create social/environmental meanings that may be contrary to the intention of the piece. This means that the opera can either be set in that vague non-time-specific no-man’s land that opera does so well, or, rather more controversially, it is open to rather more extreme interpretations. The staging here by Sven-Eric Bechtolf for the Opernhaus Zürich in 2004 consequently can be seen as being either wilfully bizarre or just perfectly suited to the unusual nature of the opera. In outline, the story is not that complicated. Lost in a forest while hunting a boar, Prince Goland discovers a young woman, Mélisande, weeping by the side of a lake. He doesn’t know who she is, although there is a crown at the bottom of the lake, but rescues her and they are married. Mélisande however forms a closer attachment to Goland’s brother Pelléas, a relationship that, inevitably, is to have tragic consequences.

There is however more going on between the characters than is evident on the surface, each of them having hidden natures, each of them unable to fully relate to or communicate with one another. As a means of bringing this out, Bechtolf places the characters in some kind of winter fairy-tale kingdom to emphasise the nature of their isolation, while he employs full-size look-alike dummies for each of the characters to act as doubles for them, the characters more often speaking to the dummy counterparts and pushing them around in wheelchairs than relating to the actual people. It all seems rather obvious and it’s tempting to see the device as just an expression of how people are puppets being used by others for their own purposes, but that is also too obvious and, in a symbolist work where there is just as much emphasis on objects – hair, rings, towers – it’s appropriate that the characters are objects themselves (the split into halves indeed being the original definition of symbolism). In this light, and on a non-rational basis, what appears to be a bizarre conceit proves to be uncannily effective, and when the characters do communicate directly with each other – as opposed to interacting with dummies – it does force you to take more notice of what is being said.

How much you will buy into this depends largely on your tolerance for high-concept modern stagings and how much credence you give to the symbolist movement, since other than perhaps in the film work of Antonioni and his disciples, their style doesn’t have a great deal of relevance or influence and is not held in great regard nowadays, certainly not from a literary viewpoint. It’s important to note however that the staging is not a distortion of the intentions of the opera on the part of the producers, but rather, if it doesn’t adhere to the letter of the work, it is nonetheless perfectly in keeping with the spirit of it, and certainly matches the spirit of Debussy’s musical composition. Making use of a revolving stage, the production is certainly effective in its dreamy fluidity, but it’s also exceptionally well sung, particularly by Rodney Gilfry as Pelléas, but Isabel Rey as Mélisande, Michael Volle as Goland and László Polgár as King Arkel are all marvellous. The orchestra playing is superb, particularly in the excellent High Definition sound reproduction on the Blu-ray.