Bayerische Staatsoper, Munich, 2012

Kent Nagano, Carlus Padrissa, La Fura dels Baus, Claron McFadden, Anna Prohaska, Jussi Myllys, Willard White, Gabriele Schnaut, Kai Wessel, August Zirner

Internet Streaming, 3 November 2012

The first opera for the new 2012/13 season of the Bavarian State Opera in Munich was something of a bold statement of intent. A new modern opera receiving its world premiere, Babylon is an almost three-hour long epic with lavish production values that seem to fly in the face of European austerity measures and defy restraints on budgets in the arts. With a libretto written moreover by philosopher Peter Sloterdijk and music composed by Jörg Widmann, the 39 year old student of Hans Werner Henze, it seemed something of an omen that Henze should die mere hours before the opening performance, leaving the way for his protégé to make a mark on modern opera with an important new work. There was consequently a weight of expectation surrounding the opening of Babylon, and with a visually astonishing production from Carlus Padrissa of La Fura dels Baus that was perfectly in accord with the colourful nature of the work, the opera certainly made an impression, even if its impact was inevitably somewhat reduced for those watching it (and experiencing technical difficulties) with its Live Internet Streaming broadcast on the 3rd November.

Babylon relates back to Biblical times and ancient Mesopotamian mythology, to human sacrifice practiced by the Babylonians and the repudiation of it by the Jews, to the destruction of the walls of Jericho and the founding of urban civilisation. Central to the work then, with its invocations of the mystical number seven, is the formation of order out of chaos, an order associated with numerology that is reflected in the establishment of the seven days of the week. It's a love story that is both the cause of the chaos that ensues as well as what brings about redemption and order. Widmann's opera opens then with a prologue showing a scene of apocalyptic devastation, a scorpion man walking through the ruins, before the Soul arrives to open up the first of the opera's seven scenes, mourning the loss of Tammu, a Jewish exile living in Babylon who has fallen in love with Inanna, a Babylonian priestess in the Temple of Free Love.

The visions of chaos and destruction continue unabated as Tammu lies with Inanna, and is awoken through love and some herbal induced visions - the seven planets and even the Euphrates itself bearing testimony - to the truth that their world is founded on chaos that the Gods have unleashed upon the universe. (Mozart and Schikaneder's The Magic Flute is obviously drawn from the same sources - Tamino and Pamina recognisably relating to Tammu and Inanna). It's this chaos that the Babylonians hold at bay through human sacrifice, a "truth" that is hidden by Ezekiel in his teachings of the Jewish law and the stories of Noah and the flood. When Tammu is chosen as the next human sacrifice however and is executed by the High Priest following the New Year celebrations, Inanna joins with the Soul in her lament for his loss. Inanna pleads with Death to allow her to journey to the Underworld to bring Tammu back.

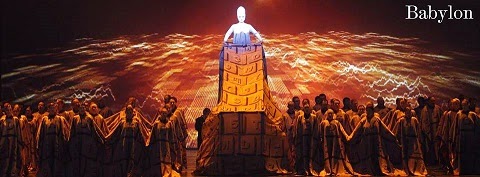

Undoubtedly the most striking thing about Babylon is the direction of this vast undertaking by Carlus Padrissa of La Fura dels Baus, with its spectacular production designs by Roland Olbeter. Every element of the ambitious libretto, with all its mystical symbolism, dreams, visions and mythology, is presented in visual terms that aren't merely literal, but connect on an intimate level with the music and the concepts wrapped up within it. In its seven scenes (with a prologue and an epilogue) a Tower of Babel is erected and destroyed, the seven planets appear during Tammu's visions, the River Euphrates is personified as well as represented by a stream of words and letters that flood and overflow, seven phalluses and vulvas appear with seven apes during the New Year celebrations, flaming curtains give way to sudden downpours during the sacrifice of Tammu, and Innana wades through a seething mass of (projected) bodies, discarding seven garments (a dance of the seven veils), as she journeys into the Underworld. The stage is never static, there's an incredible amount going on, with extraordinary detail in background projections, processions, with supernumeraries in all manner of costumes and guises.

Babylon is therefore, opera in its purest sense. The music and singing alone don't stand up on their own, the spectacle alone isn't enough, but the work needs each of the elements of the libretto, the music, the performance and the theatrical presentation to work together and in accord to put across everything that is ambitiously covered in the work. Widmann perhaps takes on too much across its great expanse of scenes and musical styles - cutting suddenly between twelve-tone dodecaphony, jazz, cabaret and Romanticism - to the extent that it can feel episodic and difficult to take in as an integral and consistent work. Babylon however has a solid foundation in its subject, in Kent Nagano's marshalling and conducting of the orchestra of the Bayerische Staatsoper, in Padrissa's impressive command of the visual elements, and in Anna Prohaska's extraordinary performance as Innana that goes beyond singing. Babylon is opera in the purest sense also in that it undoubtedly needs to be experienced in a live theatrical context in order for its full power to be conveyed. On a small screen, viewed via internet streaming, the rich scope, scale and ambition of the work were nonetheless clearly evident.