George Benjamin - Picture A Day Like This

Festival d’Aix-en-Provence, 2023

George Benjamin, Daniel Jeanneteau, Marie-Christine Soma, Marianne Crebassa, Anna Prohaska, Beate Mordal, Cameron Shahbazi, John Brancy, Lisa Grandmottet, Eulalie Rambaud, Matthieu Baquey

ARTE Concert - 14 July 2023

I have to say that my first impression of the new opera from George Benjamin and Martin Crimp premiered at the 2023 Aix-en-Provence Festival was that it appeared to be a slight work; a simple story, a fable, a fairy tale with a fairly obvious moral and meaning. Such thoughts were also there to an extent while viewing the previous two operas, Written on Skin and Lessons in Love and Violence, at least in as far as they seemed overly studied and mannered, removed from the everyday. Both those operas however nonetheless left a great impression and have rewarded further listening for detail and substance, and I have little doubt that Picture A Day Like This will be the same.

Running to around 65 minutes Picture A Day Like This is certainly shorter and perhaps even slighter than the previous two operas by Benjamin and Crimp, but it is by no means a lesser work, since it deals with deep emotional reaction to difficult human experiences and situations. It doesn't employ a full orchestra, nor does it appear to take in the wide range of emotions and dramatic action as the previous two works. Rather it's a chamber opera with a smaller cast and orchestra, although it does have at least as few principal roles as Written on Skin. Like that work, it's equally as intense and bristling with underlying menace and unease, only here it does so in an appropriately more concentrated form. Such is the impact that it's only when you come out of it that you realise how successfully the composer and librettist have gripped you in their world.

The plot is related in the simplistic manner of a fairy-tale, but also similarly touching on deep human emotions and universal experiences the way a fairy-tale can do. And, in the opera form, that means that it has the benefit of music to delve even further, and we know that Benjamin's music is highly capable of doing that. The story relates the loss of a child by the Woman (the creators like to operate on the idea of general human rather than specific), who is so distraught she searches for a means to bring him back to life. She is told that if by the end of the day she can find a single person who is happy with their life and cut a button from their sleeve, her child will be returned to her, and she is given a list of a number of people who all seem to be living a life of perfect bliss. Evidently, their lives are not as filled with contentment as they appear to be.

The implication or moral is clearly evident. Everyone carries their own burdens, and if they appear to be happy, it's only because they have had to learn live with their fears and trauma - some more successfully than others. Ultimately, many of those strategies have failed and there is no real pleasure to be found in material possessions, in fame or success, even love has its limitations. None of these situations is comparable to living with the death of your young child, nor is it that the intention when it comes to the Woman's final encounter with Zabelle and the beautiful garden she has created to suggest that it's in any way similar to a composer's struggle with their art, but the latter suggests that is important is finding a way of living with your unhappiness, making it a part of you, not denying it.

It's a simple moral or message then, one that shouldn't need dressed up in a fairy-tale situation with intense music, but here is no question that bereavement - particularly of a child - is a challenging and multi-faceted subject to explore. The coming to any realisation is a journey that the Woman has to make and be experienced, and - to a much lesser extent obviously - the listener has to make that same journey over the course of the opera. And to be honest, that would be hard to endure over anything longer than the running time of just over an hour. Nonetheless, George Benjamin uses every minute of that to find the right note, taking care not to overload it, using space and silence as important elements to give room for the music, the situation and the content to breathe and express itself to the fullest extent. There are few if any dramatic flourishes, and nothing seems superfluous. At times the score feels like 'mood music' or soundtrack backing in the way that it rarely draws attention to itself, but it nonetheless weaves a complex way through the emotional and dramatic content.

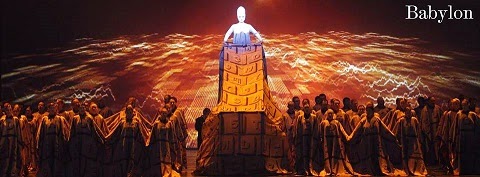

The impression that this is slight and lacking in dramatic action is probably also due to the mostly dark, minimalist stage direction, but this is also deceptive. Carefully directed by Daniel Jeanneteau and Marie-Christine Soma, as well has handling the set design, dramaturgy and lighting design, it's actually appropriate and essential that the attention isn't drawn away from the emotional impact of the primary expression of the music and the singers. As such it's highly effective, using glass and mirrors so that figures seem to appear from nowhere and vanish like in a dream. When it comes then to stressing the vital importance of the impact of Zabelle's garden then, the effects are extraordinary and almost magical. All of it contributes to enveloping you in this otherworldly place, the otherworldly place where grief takes you.

Since all the singers were hand-picked by the composer, who worked with them to play to their strengths, it's no wonder that the singing is so effective in the part it plays in this. The performances are as carefully calibrated as the music, with Marianne Crebassa creating the vital central role of the Woman. Crebassa's ability is well known on these pages, but here in such a role where a huge journey has to be undertaken over the running time of little more than an hour, it goes beyond technical ability and into timing, delivery, expression, feeling and being. Similarly, you might regret that Anna Prohaska doesn't have a larger and more showy role, but again it's a case of providing only what is essential to the work. The other singing roles of the happy but not happy people the Woman encounters - Beate Mordal, Cameron Shahbazi and John Brancy - are likewise impressive in their ability to tap into the essence of the situation and what lies behind in the music.

Benjamin, as is customary for this composer, conducts the score himself, leading the Mahler Chamber Orchestra through the dark intricacies of the score. It's a short work with few characters, few situations and minimal orchestration, but when Marianne Crebassa gazes out as the dying notes remain suspended in the air and the listener emerges out of this dream-like state, any suggestion or impression that this is a minor work is immediately erased. I've no doubt that not only does it reach as deep as Benjamin and Crimp's previous collaborations. but as well as standing on its own terms, Picture A Day Like This actually contributes another level to their body of work as a whole.

External links: Festival d’Aix-en-Provence, ARTE Concert